Dairy technology

Continued from page 2

with boosted nutrients to maintain its health.

As far as cow productivity, Trimner reported “10 pounds of milk more per heifer” and “on a whole herd basis, around 5 pounds of energy corrected milk more per animal” in the robot barn compared to the traditional parlor. Despite the increased output, Trimner stated, “the robot barn is very peaceful and very quiet.” Other technologies that maintain the calm yet productive nature of the robot barn include robotic feed pushers and collars that track cow rumination, eating, and movement. The collars alert Trimner if a cow needs attention and predict when each cow is in heat, enhancing breeding efficiency.

Along with technology in the barn, Miltrim Farms employs field technology to promote sustainable farming, a focus dating back to Trimner’s grandfather in the 1970s. Trimner said, “We love Wisconsin water, and we love using it, whether for fishing, paddle boarding, or boating. We want to keep it healthy. We want to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem.” One way Miltrim Farms works toward this goal is using variable rate spreading of seed and fertilizer to minimize field runoff. Variable rate spreading technology enables farmers to precisely allocate more seeds or fertilizer to specific areas in fields, reducing waste and runoff. On this, Trimner said, “Based on a field’s soil tests and soil type, we will try to seed it only to what it can actually produce. We strictly manage nutrients, both manure and synthetic fertilizer based on what the field actually needs.”

Looking forward, Trimner said Miltrim Farms will “continue to explore and adopt new technologies.”

Bob’s Dairy Supply in Dorchester has sold DeLaval robotic milking equipment for the past 10 years.

Owner Mark Peissig said the most common misconception of robotic milking is “the cows will be treated poorly,” and the replacement of human workers will be detrimental to the animals’ well being. In fact, Peissig reported that cows “are twice as calm in a robot barn as any other barn.” He explained that they are less stressed in a robot barn because there is minimal commotion from people: cows are not chased to the milking parlor and forced to milk at specific times. Rather, Peissig stated that cows in a robotic milking barn “get milked when they want to get milked, eat when they want to eat, and lay down when they want to lay down.”

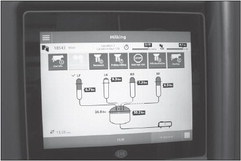

To operate this system, DeLaval robotic milking barns feature a smart selection gate. After identifying the cow by its ear tag, the smart gate determines if the cow should be milked based on the period of time since the last milking or the pounds of milk in the cow, which the robot predicts based on the animal’s production history and lactation cycle. If the cow does not need to be milked, the smart gate directs it to the feed area. When the cow does need to be milked, the smart gate opens toward the robot. Before milking, the robotic milking system preps the cow. A claw-like robotic arm attaches a cleaning unit, preparing the quarters one by one. Then, the arm individually puts the milkers in place. If a milker falls off, the robot instantly senses the issue, cleans the milker, and reattaches it. After the milkers are removed, the robot applies a protective spray to prevent mastitis. All the while, cows are given feed (if the farmer chooses this feature).

Regarding customers who implement robots, Peissig sees a variety of farm sizes. He works with farms that use a single robot and farms that use 14. His average buyer uses four. According to Peissig, robot milking systems “keep small dairies in it” by reducing the cost of labor. He added that a farm with 200 cows and four robots could be run by only two people.

The return on investment period for a milking robot is seven years. Robots are serviced four times per year, and parts are replaced according to a six year schedule. Over the course of six years, every part of the robot will be replaced. The cycle then repeats to ensure that the robots stay functional for the long run. Peissig notes that the first robot systems he sold ten years ago are still in use and “pushing 1 million milkings.” For reference, a farmer who milked 50 cows twice per day would have to milk for 27 years to equal one million milkings.

Drones in the field

In field technology, some farmers are turning to agricultural drones to spray, seed, and examine their fields.

Richard Rau, farmer from Dorchester and owner of DR Drone LLC, recently purchased a DJI AGRAS T40 agricultural drone spanning nearly 10 feet. He plans to primarily use it to spray fungicide.

“The whole goal is to do better with the acres we have,” said

See DAIRY TECHNOLOGY/ Page 11

INSTITUTING TECHNOLOGY - Farm owners such as David Trimner and Jay Heeg are always looking for the next opportunity to increase efficiency. With the help of Bob’s Dairy Supply and other businesses dealing with robotics, farms can increase cow happiness by allowing the cows to be milked on their own schedule which can lead to an increase in productivity.

STAFF PHOTO/SASKATOON DAMM Dairy technology

Continued from page 3

Rau. He explained approximately 1-2% of his corn crop is run down by the wheels of a large sprayer when he applies fungicide with it. While the 1-2% he will save from using the drone may seem insignificant, Rau stated, “at 1,500 acres you’re running down 20 acres [with the sprayer].”

Another drone advantage Rau cited was precision application of chemical sprays, saying, “We are looking for sustainability.” Rather than applying chemicals to an entire field area, Rau can target specific problem areas in need of remediation with his drone, lessening the environmental impact from these chemicals.

Rau’s drone has its drawbacks, including a relatively short battery life and an inability to operate when wind speeds are higher than 12 mph. To mitigate downtime in the field, Rau has three batteries. He explained each battery lasts about 12 minutes, and while one is in use, the other two are charging.

Although Rau’s drone will mostly be used to spray fungicide, it is capable of applying 110 pounds of seed each load, according to the DJI website. He indicated interest in seeding cover crop with his drone in the future. Whether spray or seed, the drone can cover 250 acres per day. Rau noted he will still use larger sprayers for comprehensive application of sprays as these machines are more efficient than drones.

After speaking about his drone, Rau reflected on changes in agriculture throughout his life, saying, “Kids used to stack hay bales for the neighbors during the summer. Now, I’m looking for kids to fly a drone.”

On agricultural drone technology, Matt Oehmichen, co-owner of Short Lane Ag Supply in Colby, said, “It is undeniable that this is a very popular topic.”

While agricultural drones spray fewer acres in a day than a large sprayer, there are cases in which spraying and seeding with drones is advantageous. Oehmichen explained, “If you have field conditions that don’t allow you in the field, or you have a field shape that is odd and for a regular sprayer hard to maneuver in, you take these drones and then you can spray.” Oehmichen added that a single drone “can carry a payload of 100-300 pounds of seed or chemical,” depending on the model.

Agricultural drones’ versatility comes with disadvantages. Oehmichen said, “One downside is battery life. Agricultural drones can typically do 2.5-5 acres per charge. Any operation probably finds themselves owning four to ten batteries.” On top of the cost of an agricultural drone, which is in the ballpark of $30,000, the batteries cost anywhere from a few hundred dollars to $1,000 each.

Given the high initial cost of an agricultural drone, whether investing in one is economical, depends on the farmer’s situation. According to Oehmichen, “If you have manageable acres, less than 100 acres, a drone at $30,000 could make sense.”

Oehmichen views drone operating as an entry point into agriculture for those who specialize more in technology than crops, saying, “You don’t necessarily have to have a background in agronomy to use drones in this field. If you understand tech and can do math, you can operate this thing.” However, Oehmichen did elaborate that many agronomists are making use of drone technology to garner work spraying and seeding cover crops for farmers.

Most of Oehmichen’s work with drones consists of field assessment photographs and video production for agricultural education and promotion. With regard to field assessment, Oehmichen said the benefits of a drone include “getting a bird’s eye view of weed density and seeing trouble areas of a field.” Oehmichen also uses drone captured photographs and videos to advocate for conservation efforts. He said, “I show these images to put everything in perspective: reducing runoff benefits the rural communities, from shore line owners to farmers. It’s not just the shore owners, and it’s not just the farmers, it’s everybody. Everybody has to put in their effort to reduce runoff and clean up the water.”

Other technologies

To improve field efficiency, Medford Cooperative services fields using a VRT spreader and a sprayer with individual nozzle control.

VRT stands for variable rate technology. A VRT spreader differs from a typical spreader because a VRT spreader can be programmed to spread varying rates of fertilizer on certain

See DAIRY TECHNOLOGY/ Page 12

THE MAN BEHIND THE SCREEN - Matthew Oehmichen of Short Lane Ag Supply displays a drone that is used in the agriculture field. Farmers could spend up to $30,000 on agricultural drones.

STAFF PHOTO/SASKATOON DAMM

PUTTING TECH TO USE - This agricultural drone will be used to spray fungicide over Richard Rau’s fields. The drone is capable of applying 110 pounds of seed each load.

STAFF PHOTO/SASKATOON DAMM Dairy technology

Continued from page 11

areas of a field depending on the needs of each area.

According to Director of Ag Services Carl Kass, “The [variable rate] spreader improves yields, but it also reduces waste. This way, you can get the right amount on each spot and make each spot in the field the most efficient.”

To determine the custom fertilizer needs of different spots in a field, the soil is sampled in grids by an agronomist. On this process, Kass said, “Usually agronomists take the top few inches. They take several soil cores in one grid, and then they mark that grid in a separate bag. Then they go to the next grid and do the same thing there. Those samples are analyzed for the nutrients level, and that’s how we get to our recommendations. That’s all fed into the [spreader’s] mapping system, and the mapping system can spread according to what nutrients are needed in those spots. The spreader cuts on and off depending on what level we want, our prediction of the crop, and what was in the soil when we started.”

While the sprayer is not exactly variable rate, it features individual nozzle control that prevents spraying overlap by selectively shutting off nozzles over areas that have already been covered. Additionally, the sprayer accounts for the difference in speeds on turns to ensure each area is adequately sprayed. Kass explained, “If you are in a marching band, when you are walking on a corner, your bandmates that are in your line keep a straight line. The outside person has the longest track. They have to walk much faster than the inside person. The sprayer will compensate for things like that.” Kass discussed the upside for farmers of having the co-op provide these technologies and services, saying, “The co-op is farmer owned, so farmers get patronage back when we have a good year and have good profits. That can add up to be quite a bit. The other thing is that it is shared equipment, so we can get the technology quicker than a farmer can because we do so many acres, and that helps spread out the cost of the technology.”

Looking forward, the Medford Cooperative anticipates purchasing an agricultural drone for spot spraying. This drone will also be equipped with an infrared sensor, which can be used to monitor crop health through changes in crop temperature.”

Aside from milking and field technology, artificial insemination continues to bolster breeding efficiency and herd quality.

Sandy Stuttgen is the Agriculture Extension Educator at the UW-Madison Division of Extension Taylor County. She explained artificial insemination technology and the current landscape of dairy farming.

Artificial insemination, which is used by 90% of dairy farms, allows farmers to selectively breed for female calves from the best cows and bulls. This way, the investment of raising the dairy calves will only be made on calves with high return. While the specific traits farmers are looking for depend on their operation, high milk output is universally sought. Additionally, robot barns seek cows with good udder confirmation to maintain high milker attachment rates by the robots.

A common challenge in dairy farming is finding workers. Stuttgen pointed to the last five years as having a particularly severe labor shortage. One potential solution is to replace labor with automated robot milkers. Another problem on the horizon is a lack of replacements for farmers who are aging out of dairy. Stuttgen noted that the average dairy farmer is age 52 and has been farming for 26 years.

In spite of these challenges, Stuttgen said the farmers she talks to are “generally optimistic and seem to want to be farming.” They are “willing to learn” and network with each other through organizations to stay informed. As far as technology on farms, Stuttgen said farm technology “adoption and access is faster than ever” thanks to the internet and that Taylor County is “on-par” with the rest of the dairy industry’s technological advancements.

While technological innovations show promise, some farmers are avoiding the cost of going all in by balancing their bottom lines with a blend of new technology and traditional practices.

Ryan Klussendorf of Medford operates a family farm of 120 cows. He rotationally grazes his cows on 200 acres.

Klussendorf has been aware of robotic milking systems since 2008 but chooses not to purchase them. On his decision to stick with a traditional parlor, he said, “Everyone has what works for them. This works for us.” Klussendorf listed the high cost of robotics as the predominant deterrent, stating, “It’s a huge capital investment.” He noted that his parlor is paid off, so the idea of incurring debt to replace a functional and paid-for system is unappealing. Additionally, his existing infrastructure is not conducive to a shift to robotic milking. While he has seen grazing systems implement robotic milking systems, his parlor is not centrally located, which would not be ideal for a robotic milking system. Again, changing this would require a massive investment.

Although he chooses to milk in a traditional parlor, Klussendorf employs other technology to augment the quality of cow care. All of his cows wear an ear tag that measures their reproductive cycle, temperature, rumination, eating, and movement. He evaluates this data through an app on his phone, which alerts him of any abnormalities. The health alerts typically precede any outward symptoms.

To maintain pasture quality, Klussendorf makes use of another app on his phone that measures the height of the grass through a device on his four wheeler and suggests pasture rotations. A pasture rotation means adjusting the fences so the cows have access to a select area of grass. This is done so areas that need time to replenish are not overused.

Klussendorf manages his field so that “everything is working together for the benefit of the ecosystem, cows and people.” Some sustainable methods he practices in his field are cover cropping, no-till planting, and the creation of pollinator habitats. Cover cropping means planting crops aside from the harvested crop, such as corn, to enrich and maintain the soil. In a no-till system, farmers do not till the soil, limiting erosion. According to Klussendorf, no-till combined with cover cropping gives “flexibility with extreme weather” by “building organic matter and soil structure.” As far as pollinator habitats, Klussendorf puts “native plants and wildflowers in unproductive areas” of his field to improve the overall ecosystem.

Artificial intelligence on the horizon “Artificial intelligence is going to change dairying dramatically,” said Mark Peissig, owner of Bob’s Dairy Supply.

Peissig explained that artificial intelligence makes predictions about each cow’s health by using data gathered from an ear tag and robotic milking system about each cow’s movement, food consumption, and milk content. The data is sent to a cloud and compared to every other herd in the world. From the worldwide data set, artificial intelligence projects each cow’s health. One goal of using artificial intelligence is to be able to forecast if a cow will be sick at least 48 hours in advance of symptoms. This way, preventative care can be administered. While this technology is still in development, Peissig noted that “it is just the start.”

David Trimner, general manager of Miltrim Farms also emphasized artificial intelligence’s burgeoning application in dairy, stating, “I am very excited to see as AI continues to develop how that’s going to change the farm industry,” and “autonomous tractors are not that far away.”

When describing the impact artificial intelligence will have on Miltrim Farms, Trimner explained, “There are certain tasks that when AI progresses far enough it will make the decision making and management of them much easier. Particularly on the camera side, using camera images to monitor things on a higher level. Another big one I think about is how you utilize chemicals to the best of your ability. You may use one-tenth the amount of a chemical because of how precise it is.”

Medford Cooperative anticipates using artificial intelligence technology. Carl Kass, director of Ag, said, “It’s going to be on the horizon. It’s the track we are trending to. We will [implement it], but I think that’s a few years away for us.”

A recurring theme of efficiency underlies all of these technologies, whether it pertains to labor, resource usage, or crop growth. If there is one takeaway aside from interesting technology developments, it is that artificial intelligence, with its unprecedented efficiency and precision, has the potential to entirely transform the dairy industry (and every other industry) very soon.

It remains to be seen what impact these changes will have on the future of farmers and rural communities.

Ryan Klussendorf