Helping say goodbye

By Cheyenne Thomas

In his more than 32 years in the funeral business, Ron Cuddie has helped thousands of families through what is often the most challenging experience of their lives: saying goodbye to a loved one.

Owning and operating Cuddie Funeral Home in Loyal, Greenwood, and Thorp for many years, Cuddie has come to know many community members while making a family’s final goodbyes more personal and heartfelt and allowing those grieving the chance to begin the process of healing.

Cuddie, a native of Washington state, didn’t start out working as a funeral director. Before coming to Wisconsin, he worked as an engineer building aircraft. It was a job that opened his eyes to the kind of career he didn’t want in life, one which lacked that personal touch and sense of connection with another person that he truly sought in a job.

“The job that I had was at Boeing, and it was boring,” he said. “You would have a job that could actually be taken care of by one or two people that was divided up among a hundred employees. It was a very menial job. I’ve always been a people person, so sitting in a room with 200 people in other similar rooms was just not for me.”

He was able to change career paths after meeting his first wife, whose father was a funeral director from the Loyal area. At one point, Cuddie said he volunteered to help out for one week at the funeral home, and it was in the final moments of that first week that he got his first real taste of what the job was like.

“We went the whole week without anything happening,” he said. “Then, at 12:30 a.m. on the day I was going to go back, we got a house call for a woman who had passed away, 92 years old. We embalmed her and that was my first experience.”

After that first experience, Cuddie found himself unable to go back to Boeing, instead studying the ins and outs of the practice to pursue a career as a funeral director. For a time, he was in Milwaukee as a funeral director before he came back to the Loyal area and bought the Loyal and Greenwood funeral homes from Patty Rinka in 1999. A year later, he bought the funeral home in Thorp, and he has since operated all three locations.

Since then, Cuddie has become almost a jack-of-all-trades through owning and operating the funeral homes. There are many layers to the practice, he said, from the business aspect to taking care of the deceased, and organizing end-of-life services and other paperwork for families. It’s more than a full-time job; it’s a way of life.

“As an owner, you’re there 24/7,” he said.

See CUDDIE/ page 17

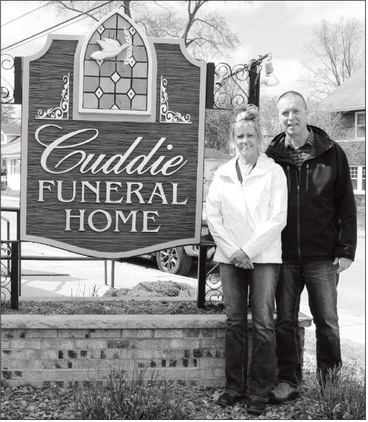

HERE TO HELP - Ron Cuddie and his wife, Susan, stand outside their familyowned funeral home in Loyal, one of three locations in Clark County.

STAFF PHOTO/CHEYENNE THOMAS Cuddie

Continued from page 16

“It’s not really all that different from being a farmer. You’re available 24 hours a day. When the phone rings, you go.”

A familiar presence

Reflecting on his experiences as a funeral director, Cuddie said personal connection is one big tiling that stands out as a difference between rural end-of-life services and services offered in large cities. When he was in Milwaukee, he said he often noticed how the practice was treated with speed and lacking that personal touch, with embalming being done in less time by embalmers, which is noticeable in their work. “I have seen some embalmers say, ‘I embalmed this person in 45 minutes,’ and I would just look and say, ‘Yup, it sure looks like it,”’ he said. “There isn’t that care given. It’s treated almost assembly-like. But here, you get to know the people; you know what they look like and you do your best to make them look as close to, if not better, than they looked in the hospital before they passed.”

This practice extends beyond taking care of the body of the deceased, Cuddie said. Another tiling he noticed in larger cities was the lack of consistency when dealing with families. From the first phone call to the final services, he said a family would sometimes work with multiple funeral directors, while in a rural practice like his, a family works directly with him from beginning to end.

“In a big city, there’s no continuity,” he said. “On the first day, you can be working with one funeral director. Then the next day, working with a different one and yet another one on the day of the funeral itself. You could have three or four different funeral directors work on the same family’s funeral. But here, you know so many people, it’s like family.”

Challenges

When Cuddie first started in the practice, he said one of his biggest challenges was not really knowing the families of the deceased. Without that personal connection or understanding, he said it made it hard to make sure the families got that personal touch in their final goodbyes. Over time, however, he came to know the people he serves, which in itself has come with its own share of struggles.

“When you first start out, you don’t know anyone,” he said. “But when you get to know the people, it becomes easier. But it does get harder the older you get. There are times now when I am burying people who were my friends. There will eventually come a day when I won’t be able to do this anymore.”

Oftentimes, the circumstances of a person’s death makes a funeral hard to do. The passing of children, Cuddie said, is especially hard, and there is a noticeable difference between families who lose children to a premature death compared to families who are arranging the burial of an older relative.

“There are ones that are hard,” he said. “I remember one time I had to do a funeral for a child that was 10 years old. I’ll never forget that. Especially when you are at the age when the child who died is the same age as one of your own. You can’t help but think, ‘This could have been my child.’ Working on kids’ funerals is hard. A lot of the time, I do funerals for older people, ones who are 80-90 years old, and they had a long and fulfilling life. Those times are when people will laugh and tell stories about the deceased. A child is different. The families are traumatized; they’re distressed. Oftentimes, there’s not a lot of talking that is done.”

When it comes to overcoming those types of challenges — whether working to complete the funeral of a child or someone he knows — Cuddie said it often helps him to think about the work itself, putting in as much care as he can into the entire experience and adding that personal touch he knows helps the family through their grief.

“I always think to myself that if I’m doing it, I know it will be done right,” he said. “Sometimes it’s hard, but you work through it and you look back when you’re done and you know it’s going to be OK because you know you did your best. I always think it’s better for me to do it than to have someone who didn’t know them who won’t put as much of an effort in to do it right.”

The grieving process

As a funeral director, Cuddie said he sees firsthand the grieving process that each family experiences. Looking at the work he does, he understands the importance that a funeral holds in helping a family gain closure. For many, that comes with a typical funeral service, where the body is able to be viewed, but in some instances of tragedy, he said he has taken other approaches to provide those families a sense of closure.

“I remember there was one time that I did a funeral for someone who had been in an accident. He had been run over by a semi carrying cattle and the car had been crushed completely,” he said. “It had taken them three hours to cut him out of the car and by the time I got to see him, his right arm was the only part of him that wasn’t broken. There wasn’t a way to have an open casket, but the mom wanted to see him. So I covered him with a sheet, everything except his right arm, and explained the situation to her. She came in and held his hand for about two minutes, then came back to me and said, ‘Thank you. I know it was him because he had a tattoo on his arm.’And that was all she needed.”

The future

As the Baby Boomer generation continues to get older and pass away, Cuddie said he expects things will continue to change. When he first started, he said traditional burials were the most common type of funeral he would arrange. Today, those are becoming less and less common, as cremation now makes up between 60-65% of funerals that he arranges.

“The families are often far apart,” he said. “They won’t be able to get together for months and so they have a cremation when a family member dies and hold the funeral later on when they can all meet for the service. I used to do only two or three cremations a year, but now I do more.”

Religious ceremonies too are becoming less common for funerals.

“They don’t do funerals like they used to,” he said. “Some of these families aren’t religious and they don’t want a funeral. It does affect things.”

Even as Cuddie continues to adapt his practice to meet these changes, one thing he said he will continue to keep in mind is the importance of his work in helping families find closure and healing in the midst of their tragedy.

“Some people call it its own ministry, but I try not to view it that way,” he said. “I want them to be able to remember their loved ones as they were, and it feels good to be able to help them have that closure.”