THE CURD IS THE WORD

It’s just after 8 a.m. on an early June Friday morning and a fresh batch of cheese curds is ready to come out of the vat at Nasonville Dairy’s Curtiss cheese factory. They’d better be ready, the day’s first customers are already asking for them.

A worker quickly snatches enough curds out of the vat to fill a few 1-pound bags to meet those first custumers’ needs as the rest of the Nasonville crew follows its daily routine. There will be 1,100 pounds of curds to process by morning’s end, and by the time the store along Highway 29 a mile east of Curtiss closes, they’ll be gone. Some will have been shipped to gift shops and convenience stores elsewhere, but many of this day’s squeaky-fresh curds will have been grabbed up by customers whizzing along the state highway or by families stocking up for graduation parties. This is Wisconsin, after all. The curd is the word.

And at Nasonville’s Curtiss plant, another word for the curd is champion, as licensed cheesemaker Kevin Rachu’s entry in the recent World Cheese Championship was selected as the third best.The entries were judged on flavor, body texture, uniformity of the curds and other aspects, and Rachu’s entry was just a few tenths of a point short of the World Champion entry.

By way of sales, Rachu and the Curtiss Nasonville crew already knew they had a champion product. Especially in summer, the curds vanish out of the store cooler as fast as the vats can produce them. Rachu fills two vats with 22,000 pounds of milk per day, with each 10 pounds of milk ending up as a single pound of cheese. The Curtiss curds are packaged into 10-pound and one-pound bags, and are often still warm when they began to sell.

Rachu starts the 4-hour batch process at 4 a.m. “Roughly around 8 o’clock, we should have some curds coming out of here,” he said. “A lot of times we’ll have people here at 10 after 8 looking for their curds.” They won’t last long.

“There are days we may run out of curds,” Rachu said. “We’ve got it pretty much dialed in that we know how many to make.”

The curd process is relatively simple, and much the same as it’s been since Rachu first started working for the Nasonville Dairy Marshfield plant at the age of 16. He’s been making curds in Curtiss for the past dozen years or so, and starts each day by pasteurizing the raw milk that’s collected from area dairy farm bulk tanks. The milk is heated to 161.5 degrees and held there for 15 minutes to kill any bacteria, and is then loaded into the vats.

Starter cultures are then added for flavor and pH levels. Next comes the rennet, an ingredient that will convert the raw milk from a liquid into a mixture about the consistency of pudding.

“It’s not real thin, and it’s not real, real thick,” Rachu says of the product at that stage of the process.

A cutter is then passed through the vat to slice the mixture into pieces of about 1/4 inch. They are then stirred to prevent them from sticking together and cooked at 101 degrees. After the curds are cooked, excess whey is drained off and the now solid mixture is cut into slabs. They’ll be allowed to compress for a time, then ran through a shredder that dices them into curd shape. Salt is mixed in as the curds are stirred a time or two more, and they are then ready for packaging.

Nasonville also sells flavored curds with varieties such as jalapeno pepper, cajun, garlic and dill, buffalo and taco. Flavors are added after the curd-making process, though, with powders, etc. mixed in the bags with the curds.

Nasonville Dairy’s curd recipe stays the same for each day’s batch, although several different starter cultures are used. It’s the cultures and even the particular farm from where the milk comes from that may alter a day’s batch flavor. Like those from other factories, Nasonville’s curds have their own unique taste even though their process/recipe may be similar.

“The flavor of ours can obviously taste different than somebody else’s,” Rachu said.

He did not make a special batch to enter into the World Cheese Championship. Rather, Rachu said he pulled a sample from a typical day’s run and let it stand as is.

“I did not pick a day,” he said. “It’s pretty much the same every day.”

Rachu said he strives with each batch to produce uniform-looking curds, and is careful not to add too much salt, which can make a curd’s exterior hard, or too little, because then they’re “just blah.”

“I think we have it dialed in quite well,” he said. Rachu is also proud of the fact that Nasonville’s Curtiss plant still makes curds the way they have been for decades. Other factories are more modernized, but at Curtiss, there’s still a lot of personal touch that goes into each batch.

“I’ve been around learning that since way back when,” Rachu said. “We’re still making them the handson old way.”

That way is apparently good enough for the World Championship Cheese contest judges, as well as the folks who pile into the Curtiss store each day looking for a bag of classic Wisconsin curds. They’ll come for sure on Good Friday, Rachu knows, as they pass by on the way to a family meal. And they always some when the Minnesota Vikings play the Green Bay Packers, as fans driving between Titletown and the Twin Cities often stop for a bag.

“We look at the Packer schedule to see” when to make more, Rachu said.

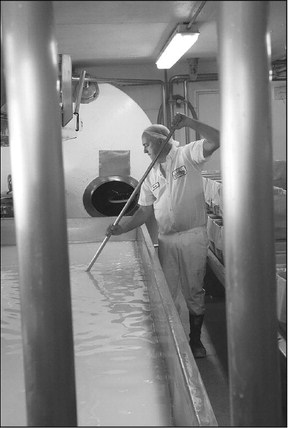

STIRRING THE CURDS AND WHEY - Kevin Rachu stirs a vat of cheese curds at Nasonville Dairy’s Curtiss plant. The curd will thicken at the bottom of the vat and the excess whey will be drained off and used for other products.