GROWING THE GARDEN OF THE SOUL

Kat Becker personally thrives running Halsey vegetable business

What do you do if you are a nerdy New York City kid growing up around Columbia University but in love with physical challenges, including sports?

Kat Becker’s answer is that you teach women’s studies and sociology at UW-Marathon County in Wausau for seven years, and, as a next step on the path of personal growth, raise 30 different vegetables, including the best carrots possible, on the rock-littered soil of a 50-acre vegetable farm in the town of Halsey.

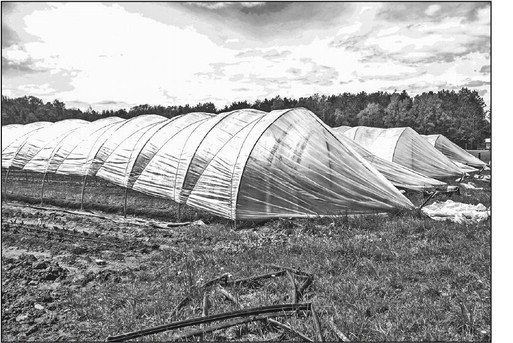

Becker and her husband, Logan, plus four part-time employees, are Cattail Organics, which supply certifi ed organic vegetables to 120 Community Supported Agriculture subscribers (depending on the season), five area restaurants, two grocery stores and five schools. The local business raises a lot of vegetables. This produce fills half a dozen clear plastic- sheeted hoop houses and pokes its heads out of long stretches of black ag plastic located on the farm’s 10 tillable acres of Magner Silt Loam. This time of year, Napa cabbage and kale are nearly mature, as is green and purplish lettuce. Long rows of garlic reach to the sky. Onions have already been harvested, carefully trimmed and loaded in black, plastic crates ready for sale. The crates, too, are filled with the farm’s unintended bumper crop, rocks.

The farm started in 2018 with a $300,000 loan. Becker’s plan was to concentrate on vegetable production. She pursued the goal with unstoppable zeal. The produce business was both an intellectual challenge, but also a physical one. It was totally Kat.

“That’s why I like agriculture,” she said. “It’s nerdy science, but physically intense. It’s like Pandora’s Box…there is just more and more. It’s exciting what you can learn.”

Becker spends a lot of the winter studying vegetable varieties, tweaking a planting calendar of her own invention and laying out plans how each species will be planted, harvested, packaged and sold. It feeds her fire. She is constantly pushing to improve product quality.

Becker, for instance, plants Bolero carrots. They seem to thrive in her farm’s heavy clay soil, forking around the rocks that proliferate in the soil. Becker said Bolero carrots have a great flavor, a great snap and are far superior to lesser quality, bleach dipped California carrots sold in the familiar twist-tie plastic bag.

Becker thinks, too, her carrots are better food and are raised in a more socially responsible way. The carrots carry traces of the local soil (“local microbiome”) improved with lots of compost and are harvested by people paid a decent wage. Her employees all receive between $14 and $18 an hour.

Becker said that most people think that production vegetables are largely harvested by machine. She said that’s not true and people labor to harvest most vegetables, sometimes not under good conditions.

Becker said she takes pride in the vegetables she grows and presents them accordingly. They are washed carefully, clipped neatly and packaged.

“We put in that extra effort,” she said. “It’s easy to make our vegetables look better than what you find at the grocery store.”

Becker said she likes her style of farming because it permits creativity. She said commodity farming, which involves USDA crop insurance, limits a farmer’s creativity. That’s because crop insurance demands planting a crop by a certain date.

Becker won’t be boxed in. She’ll forego government help in order to do her own thing.

“We basically don’t get money from the government,” she said. “If you do, it’s not impossible to innovate, but it makes it harder.”

Becker said that, like other farmers, she can be a workaholic. She, however, identifies that as a problem. A current focus is how to schedule weekends off to take her husband and three children on camping trips. Her family, she said, is nuts about fishing. The dozens of fishing rods and multitude of tackle boxes at her home provide easy proof of the claim.

Becker said she has been able to pay off her debt to “manageable levels”and continue to pursue creative vegetable production, as well as volunteer for some local causes.

It was always risky to assume that the daughter of a Manhattan psychiatrist and museum staffer who loved soccer, basketball and softball could find satisfaction growing brussel sprouts, San Marzano tomatoes and hot peppers in northwest Marathon County, Wisconsin. But Becker’s gamble has paid off.

“I am very happy,” she claimed.

WARM AND COZY ENVIRONMENT - Hoop houses at Kat and Logan Becker’s Cattail Organics farm provide a warm growing environment that allows the operation to get an early start on producing the vegetables that will be sold to the 120 subscribers of their Community Supported Agriculture business. Throughout the growing season, Cattail Organics will provide area families in northwestern Marathon County with onions, carrots, garlic, lettuce and other fresh produce.