Group seeks limit on dairy growth

Representatives of the two major farm organizations in central Wisconsin last week Wednesday told a group of over 30 people at the Abbotsford City Hall that a Dairy Together growth management plan represented the best, last hope to halt rapid consolidation of the U.S. dairy industry in the upcoming 2023 Farm Bill.

Spokesmen for the Wisconsin Farm Bureau and Wisconsin Farmers Union said the nation has lost 17,000 dairy farms since a collapse in prices in 2015, including one or two a day in Wisconsin, and called for dairy producers to unite around a proposal developed by University of Wisconsin dairy economists Drs. Chuck Nicholson and Mark Stephenson. “This is the time to get something done,” said Bobbi Wilson, Farmers Union spokesperson looking ahead to Farm Bill negotiations.” This is our last shot. Otherwise, there won’t be enough dairy farmers left to make a difference.”

The growth management plan, while not a quota system, rewards dairy producers for keeping production stable and penalizes other producers, depending on size, for increasing production beyond four percent a year. These growth dairies would pay a dairy market access fee in the single year that they increased production. The fees would get paid to the producers who only minimally increase production.

Nicholson told the Abbotsford audience the plan would improve pay prices and profitability for dairy farmers who keep production stable. The price of dairy products would increase for U.S. consumers and dairy exports would be hurt. The federal government, however, would save billions of dollars in its Dairy Margin Coverage subsidy program.

Nicholson explained the program by using the example of a dairy farm that maintained production of four million pounds of milk each year (approximately 180 cows) between 2014-2021:

_ The farm would have enjoyed a higher pay price, $17.70 per hundredweight, as well as 60 cents per hundredweight in market access fee payments from dairy producers who increased production. The farm’s total pay price would have been $18.30 per hundredweight.

_ The farm’s all-milk pay price would have increased between 73 cents and $1.41 over the 2014-21 baseline. Net farm income would have soared from a baseline of $50,000 per year to between $110,000 and $150,000 per year.

_ The program would have increased the cost of fluid milk to American consumers by nine to 15 cents per gallon. The price of American cheese would have increased between five and 11 cents per pound.

_ Due to the higher cost of product, American exports would have continued to grow, but at a slower rate. Exports would have beeen between $274 and $369 million a month less than what they would be at a lower price.

_ The federal government would have saved up to $2.6 billion in Dairy Margin Coverage payments over eight years.

Nicholson said this same farm would have been penalized if it increased production from four to five million pounds in one year but only for that year. The farm’s milk price would have dropped to $16.20 for a single year and then returned to $18.30 the next year.

Wilson said the Nicholson and Stephenson plan represented an evolved view in how to approach dairy supply management. She recalled her organization toured with members of the Canadian dairy industry across Wisconsin in 2019 to stimulate discussion about a quota system. Based on farmer comments, Wilson said a growth management plan has emerged that does not include a quota base that can be sold or that rules out any incremental dairy growth.

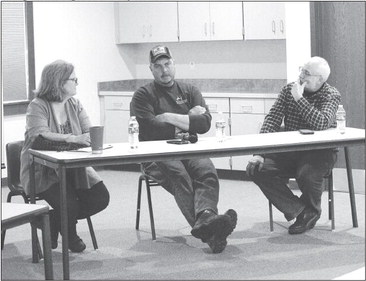

A panel discussion of three dairy producers agreed that something needed to be done to help the small and medium sized dairy farmer stay afloat, but neither producer gave a rousing endorsement of the Nicholson and Stephenson plan. Clark Turner, a Clark County dairy farmer with 120 cows, said the future of his operation is “bleak” and questioned whether there was a “viable path forward” as his son attempts to take over the family farm. Turner said the timing was right, however, for supply management given the current uptick in dairy pay prices.

Bruce Gumz, a Dorchester dairy producer with 65 cows, said the Nicholson and Stephenson plan “sounded great… it’s a good start,” but voiced a reluctance to move away from current federal government programming. He said the Dairy Margin Coverage program was “a good safety net” that needed to be maintained in the next Farm Bill.

Sarah Lloyd, a member of a threefamily dairy farm in Columbia County, said her family “can’t run fast enough on a treadmill” to manage their operation. She said better policies were needed not just to sustain small and medium sized dairy farms, but also the communities that serve them with supplies. “We need some policy to stabilize farming for the entire next generation,” she said. “There used to be dairy farmers everywhere down the road.”

The Dairy Together meeting organizers said farmers can use a computer tool to calculate how they would fare if the Nicholson and Stephenson plan was in place. That tool is available at dairymarkets.org.

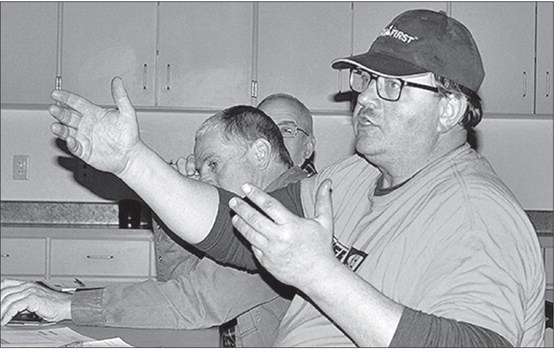

Dr. Chuck Nicholson

Dairy Together farmer panel