New game

Continued from page 8

tap up to three to four thousand trees. A quick, cursory glance at his operation shows lines of plastic piping zig-zagging through the woods that surround the former dairy farm.

He likens his double-line system to that of a feather.

“Your main part of the feather is coming downhill, and your lateral lines that approach from the trees come in at an angle, and everything is sloping downhill,” he explains. “A two percent slope is good . . . and they have found in the last few years that if you have a lot of slope, like five percent, it will actually put a natural suction on the tree, and the gravity will make its own vacuum at the tree.”

The pipes carry gallons of water-infused sap into big drums called receivers every day during the peak of the season. Two main lines bring the sap from the top of the hill, and a vacuum line connects to Loucks’ receiver and pumps the sap to a holding tank. The sap is then brought to the main hub, which holds the reverse osmosis and evaporator.

Loucks takes advantage of the features of his property, placing his receivers in natural depressions, slopes and valleys around the woods. Pressure gauges are placed at various intervals to make sure there’s enough suction to allow for the steady flow of sap.

If you listen quietly, you can even hear the sound of sap being carried through each pipe, the noise thrumming through the woods like the steady beat of a heart.

Dave has fine-tuned the process over many years to achieve maximum results.

“The first two times we set lines up, we were learning,” he said. “It’s pretty close to where it should be now.”

The trade has certainly come a long way, with innovations in technology modernizing each step in the process, turning the sap into the delicious, golden brown syrup craved by so many faster than ever before.

Which is good, since demand for the syrup continues to remain high. The Loucks are hoping it continues to stay that way.

“I do worry about over-producing. Up to now, we still have enough demand to meet production. What will happen in the next 20 years? I don’t know,” Dave says with a shrug. “We may out-produce the market, or maybe demand will keep going up. But it’s a natural product, and I think people are kinda getting away from the dextrose-based, processed stuff.”

Thankfully, Loucks hasn’t yet had a problem selling his syrup, and even though he enjoys making the syrup, he has always approached it as a job.

“It was always more of a business, because living on the highway here, we’ve sold maple syrup as long as I can remember. We would sell all that we could make. We had a real good business — all the Minneapolis and Green Bay traffic has treated us excellent over the years.”

That’s another thing that’s changed, says Dave. His customers have gone from driving down a highway to get the syrup to surfing the internet to find him.

“Up until the internet, everything was pretty much roadside traffic, up until 10 years ago. We have an excellent location, we have a good product, and a lot of repeat customers,” he said. “The summer time business was unbelievable, and they’d stop year after year, so we have a good customer base.”

Roadside traffic now constitutes just 10 percent of his sales. Outside of internet transactions, Loucks has a distributor in Milwaukee that sells his syrup to high end restaurants.

“He sells probably 20 to 30 percent of it, and then we’ve got a website. So we got old customers and new customers. Every day we’re shipping out a package.”

The Loucks ship their syrup all over the U.S., including Alaska and Hawaii. They avoid overseas sales due to the exorbitant cost of international shipping. Dave says he’s noticed that more and more people are getting involved in the business, since technology makes everything easier.

“So far, we’ve seen an increase in producers that have gotten into the business in the last 10 years because of the technology. It makes the work a lot faster. You can set these lines up when the weather is fair, and once it’s set up you just hook your line up to the tree.”

When everything is ready, and the season begins, and the temps start to climb in the spring, a temperature sensor starts up the pumps and everything begins to flow.

That’s not to say the weather isn’t still a factor, especially for those who still use the tappers, pails and open pan fires.

The weather can be your greatest friend or biggest foe, with so much of the syrup dependent on the freeze-thaw cycle of spring. But that’s not the case for Loucks and his operation.

“With the bags and the pails, you have your up years and your down years, and that’s because of the weather. Since we went to the high vacuum, we are able to produce almost the exact same amount of sap every single year.”

But Mother Nature still has her say.

“We are still dependent on the weather. We still need frost at night and a nice 40 to 45 degrees during the day.”

Passion and knowledge are also still very much needed. Even after 50 years, Loucks says he still loves what he does.

“You got to love the outdoors. That’s it. You gotta love the outdoors and enjoy being outside. I do, and it’s a good income.”

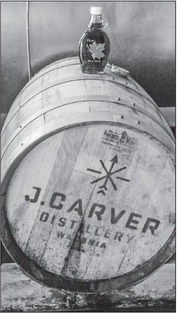

INNOVATIONS - Above left, a pressure gauge helps maintain a steady flow of sap from Loucks’ trees during the maple syrup season. Loucks has added numerous innovations to his maple syrup operation over years. He also offers new products, like syrup that’s aged in oak bourbon barrels that gives his syrup a unique flavor and aroma that carries just a hint of bourbon.