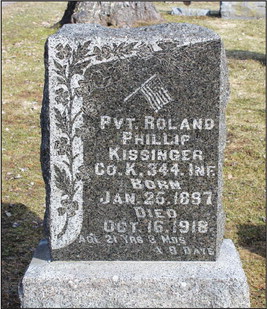

Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 targeted younger victims

Ever since COVID- 19 began making its rounds outside of China, a lot of comparisons have been made between it and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. But how similar are the two disea...

Ever since COVID- 19 began making its rounds outside of China, a lot of comparisons have been made between it and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. But how similar are the two disea...