Conviction tossed,

from p. 1

allows comments made by Ayon about then-recent events “without the contemplation of pending litigation.” The “state of mind exception” allows for comments that establish Ayon’s emotional and mental state, but not the events which may have led to that state.

The judge considered six groups of statements made by witnesses and determined that three of them were “improperly admitted” in a way that prevented Contreras Perez from getting a fair trial.

First were statements from Ayon’s friends and coworkers indicating that if anything ever happened to Ayon, Contreras Perez would be to blame. Diehn ruled that the prosecution used at least one of those statements in its closing argument to imply that Contreras Perez committed the alleged crimes, which goes beyond the hearsay exceptions.

Secondly, the judge determined that testimony regarding Contreras Perez’s alleged threats Ayon were inadmissible based on previous court decisions. Several statements that Contreras Perez knew how to make Ayon “disappear” were ruled inadmissible.

Lastly, Diehn ruled that hearsay statements from Ayon that she was afraid of Contreras Perez because he threatened her and treated her badly were inadmissible.

Prosecutors had argued that, even if some of the statements were inadmissible, the jury still would have found Contreras Perez guilty based on all of the other evidence presented. Diehn agreed that many of the hearsay statements “did not contribute to the verdict.”

“These statements contributed a small portion of the evidence presented, and none of the statements were of a nature that a jury would reasonably find them compelling,” he wrote. “The state presented other, significant evidence on these same issues.”

However, he said statements indicating that Contreras Perez had threatened to kill Ayon and knew how to “make her disappear” were “extremely persuasive evidence in the context of a homicide trial in which the body was never found.”

“Erroneous admissions of the statements very likely contributed to the jury’s verdict,” Diehn wrote. “Therefore, the error was not harmless.”

Diehn’s decision also addressed three other reasons that Grotelueschen provided for vacating her client’s conviction, including questions as to whether the alleged crimes occurred in Clark County, whether Contreras Perez was unfairly implicated because he invoked his right to remain silent and whether he had inadequate legal counsel.

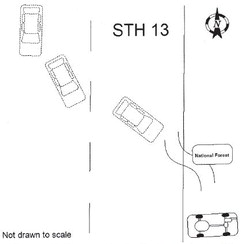

Testimony by Ayon’s friends and co-workers was not the only evidence presented at trial. Prosecutors also used cell phone data to track Contreras Perez’s movements at the time of Ayon’s disappearance, showing that he was likely in the area of Unity, where she was last seen by a friend.

The prosecution also called attention to the defendant’s movements after the disappearance. Just a couple days after Ayon went missing, Contreras Perez left the farm where he had been working for 18 years and never returned. He left just a few hours before police investigators arrived to question him.

Contreras Perez remains in jail on a $1 million cash bond, and no further court dates have been set at this point, according to online records.