Seale shares her nightmare story since CWD detection

When Laurie Seale noticed last July a 6-year-old doe on her Maple Hills Farm facility didn’t seem well, little did she know that would be the start of a yearlong nightmare that would end her successful career in deer farming, wipe her out physically, mentally and financially and, most importantly to her, bring what she says was an undeserved end of life to her herd of 300 deer.

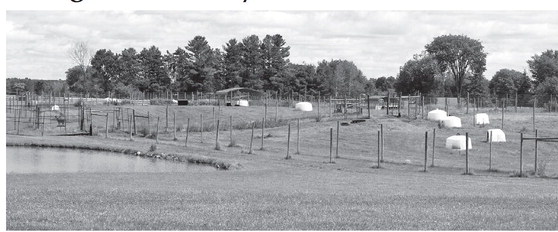

In 33 years, Maple Hills Farm, a 40-acre facility located just outside of Gilman, had become a top producer of majestic trophy bucks, both typical and non-typical. Seale’s knowledge of genetics gained in those years had produced some unbelievable bucks that had sold for top dollar to hunting ranches throughout the country. And with that genetic knowledge, she believes she was closing in on cultivating a herd that was building a resistance to chronic wasting disease (CWD), the deadly disease first found in Wisconsin’s wild deer herd in 2002 that has slowly and steadily spread in Wisconsin’s wild and captive deer herds.

She didn’t quite make it. That 6-year-old doe was found dead of pneumonia the next morning, which Seale said is a common cause of death of farm-raised deer, though how quickly it died was peculiar. By rule, any dead animal on a Wisconsin deer farm must be tested for CWD. Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) records show the sample was collected on July 24, 2021 and on Aug. 11, DATCP sent out the statewide news release saying the deer tested positive for CWD and the farm was placed under a required state quarantine. On Aug. 30, the Department of Natural Resources announced a three-year baiting and feeding ban on deer in Taylor County would start on Sept. 1, 2021.

“Total shock,” Seale said in an Aug. 1 interview at her now-empty farm. “Even when they called me, the Department of Ag told me they were shocked that it was a positive. I was a closed herd for seven years which means I wasn’t bringing in any animals. So I didn’t import the disease. I’m double fenced. Supposedly there is no CWD in Taylor County. I felt I was taking every precaution to prevent the disease. I was shocked. The state was shocked. I felt I was one of the safest farms to buy animals from.”

A year after that doe came up ill and two weeks shy of a year from the date her farm was quarantined, Seale’s herd of exactly 300 deer was depopulated July 25-28.

As painful and inevitable as it was, the depopulation process, Seale said, didn’t have to take a year. She said lengthy haggling with state government cost her hundreds of thousands of dollars, it cost state taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars and several healthy animals were the ones that paid the ultimate price.

“I don’t want people to feel sorry for me or have pity on me,” Seale said. “I want people to understand that my animals paid a high price for whoever is trying to punish me. ... Trying to feed 300 animals –– I haven’t had a paycheck since April of 2021. So they have mentally, emotionally and financially destroyed me. It’s sad and something’s gotta change. We can’t keep treating CWD like it’s the radioactive material that it’s not. It’s been here for 20 years. It’s not going away and they can destroy every deer farmer in the state and it’s not going to stop the disease. It’s here to stay.”

‘CWD is real’

Seale wants to make it clear she is not minimizing CWD’s impact on whitetailed deer. If her herd was doomed, one of her goals was for the scientific world to be able to use the herd to learn as much as possible about the disease.

“I want to say the disease is real,” Seale said. “I’ve never witnessed so much pneumonia in my adult deer as I have in the past year.”

Since that first positive, Seale said the number of positives on the farm was approaching 15 and she fully expects more positives when results come back from the depopulation.

CWD is defined as an infectious nervous system disease of deer, moose, elk and caribou. It belongs to the family of diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) or prion diseases. Prions are abnormal forms of a normally-occurring protein. Infection occurs by conversion of the normal prion proteins to the abnormal proteins. A slow accumulation of the abnormal proteins in deer tissues leads to clinical signs of the disease taking 12-18 months to show up. The prions are highly resistant to degradation. Once they are present, they don’t easily go away.

Signs of a diseased deer may include drastic weight loss, lack of coordination, excessive thirst and lack of fear of people. Seale claims she has seen those symptoms in deer on the farm that had brain diseases, but she didn’t see them in the deer that tested positive on her farm in the past year.

The state quarantine prohibited the entry and exit of any deer from Seale’s property and, because of that, she ran into roadblocks in attempting to ship out any part of any deer for analysis. She said CWD research labs at Texas A& M and Iowa State University badly wanted brain samples, but she was told in a Nov. 17 email from Amy Horn-Delzer, DATCP’s Veterinary Program Manager under no circumstances could brain mamining terial leave the farm. She did, in that email, receive permission from DATCP in November for certain diagnostic laboratory samples to move from her farm to Texas A& M or the Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratory under strict conditions.

Seale’s observations made her question what the disease actually does to deer.

“I’m not seeing a brain disease. What I’m seeing is pneumonia,” Seale said. “I was told I had CWD in August. It took them three months to agree to let me send lung tissue off my farm because the drugs that normally work for pneumonia weren’t working on my farm. You need to find out what kind of pneumonia you’re dealing with and what drugs to use. In the meantime in three months, I did lose animals because I didn’t know what to treat them with. We don’t know at this point if there’s a correlation between the pneumonia and CWD. But there’s something there.”

Seale said she requested to keep some of the animals she was breeding for CWD resistance for further research and was denied. Being told the animals were her property up until the time they were euthanized, she and her veterinarians attempted to collect blood, tissue and rectal samples for research during depopulation but were denied on the first day. She got written approval from state veterinarian Darlene Konkle to collect the samples on day two. Almost all of the depopulation took place July 25-26, with a few fawns that didn’t follow their mothers to the handling facility being the last animals put down on July 28.

“We lost at least 100 animals on Monday that had such CWD resistance,” Seale said. ‘You can’t go back and bring them out of the pit. I’m just sick. I can’t even sleep at night knowing that research was thrown away. I don’t understand why they fought the research on my farm so bad. The vets were frustrated and disgusted.”

Seale said she tested all of her does and breeder bucks over the years, deter- their genetic markers.

“Once you know what your markers are on your does, then you can bring in semen from bucks or breed with breeder bucks that have the resistance,” she said. “That’s how you breed out of it. I wasn’t culling my bucks because I figured I had time to cull them at a hunting ranch. So what I was doing was culling my susceptible does that I wasn’t breeding. I think I had a dozen GG does still on my farm, which were some of my best genetics but they’re some of the most susceptible (to CWD). I just figured I had one more year and it caught me. It was a GG doe that caught me. What I’m noticing in my bucks was it hit the GG bucks hard, so there’s definitely a correlation.

“We’re going to learn a lot from my herd but because they stopped me collecting the samples we’re not going to get nearly as much as we needed to,” Seale added later in the interview. “And that’s my frustration. We’ve got to work together to solve this disease. We can’t keep fighting against each other, hunters against deer farmers. We want to help the hunters as much as possible. Our research is not just for us. We want solutions and we’re trying and we can’t get any funding from the government.”

Unable to move bucks

The other key battle Seale fought and lost with state officials was her request to move her bucks to CWD-positive hunting ranches last fall as a step toward depopulation. There, she felt her bucks could “die with dignity,” while being harvested and tested for CWD without taxpayer expense.

The timing of the first CWD-positive deer was good in one respect because it happened before potentially infected bucks could have been broadly shipped to non-CWD areas. But it was a curse as well for Seale.

Fall is when bucks are at their peak and sold and transported to hunting ranches, bringing in the vast majority of the revenue for the year. The quarantine shut that down. DATCP’s Division of Animal Health intially supported moving bucks to a CWD-positive hunt ranch, with Apple Creek Whitetails of Gillett being the likely destination. Seale obtained an email through a Freedom of Information request that went from Konkle to DATCP secretary Randy Romanski and others that asked for approval as soon as possible and required that the bucks be harvested on the ranch and sampled within 60 days. Seale met with DATCP officials in Madison on Oct. 14 to discuss

“Total shock. Even when they called me, the Department of Ag told me they were shocked that it was a positive.” — Laurie Seale