Depopulation

her options. She finally got a letter dated Nov. 11 from Romanski denying the request.

“After another extensive assessment of the risk factors involved, DATCP will not allow movement of live animals from farms currently infected with CWD,” Romanski wrote in that letter. “In our assessment, the risk of moving animals from a premises confirmed with CWD outweighs any potential benefits. The most serious risk is spread of CWD from a known infected farm, causing increased levels of CWD prion and environmental contamination in destination herds and areas.”

By then it was breeding season and it was too late.

“I was so stressed because I couldn’t cut the antlers because I was hoping they were going to change their minds and let me move my bucks,” Seale said. “Mature bucks fight like crazy, so I lost a number of deer from fighting. And those mature bucks all came back non-detected. So if they would have at least let me move them I would’ve had the money to pay the feed bills instead of having to borrow money, cash in my retirement plans, sell my equipment.

“I had four positive hunting ranches that wanted my bucks,” she added. “I’ve built one of the best-known typical genetics in the country. I prided myself for being well-known, in 33 years being a female in a man’s world. I was proud of what I raised. I had buyers lined up and I sat here and couldn’t do anything with my animals. So once the hunting season was over then I started darting the bucks with a hormone to get them to drop their antlers. My stress level was greatly reduced once they stopped fighting. Every day I went out there I held my breath that I was going to find dead animals. It’s all money out of your pocket because they don’t pay you for any of those animals that die prior (to depopulation).”

In the on-going discussions with DATCP, Seale promised to not breed in the fall if she could move the bucks. But the longer she heard nothing and then when the request finally was denied, she said she had no choice.

“I had to start taking the really aggressive ones and start throwing them in breeder pens just to keep them alive,” Seale said. “Otherwise I would’ve lost way more animals had I not done that. And I never dreamt that this depopulation would go past fawning. So even though I was breeding I never expected to have to deal with fawns this spring and I shouldn’t have had to.”

Unfortunately some of the deer that left Maple Hills Farm before the first one tested CWD-positive unknowingly spread the disease to two farms. One was traced back to a doe that left as a fawn in September of 2020 and was euthanized a year later. It was one of six animals sent to a farm in the Antigo area. Seale said none of the 50-plus other animals on the depopulated farm tested positive.

“He had not moved to any other pens on the farm and there was a 30-foot separation,” Seale said. “We begged them to euthanize the deer in that pen and if none of them tested positive he should’ve been released (from quarantine), especially because his bucks were across the road. But they killed the entire herd. More wasted taxpayers money.”

A new deer farmer bought animals from Seale in April of 2021 and two of them later tested positive. Obviously, Seale said, learning of those positive results added more sick feelings to an already bad situation.

But Seale contends her sealed trailer would have been safer to transport deer last fall than the screened trailers the euthanized deer were put on at her farm during the depopulation. She was surprised the dead deer had their heads cut off for CWD testing at a different location and not on her already-contaminated property after all the correspondence in the past year about how moving deer or parts of deer increased the risk of spreading the disease.

Depopulation discussions picked up in November with Seale being given the options of USDA indemnity, which led to the possibility of a maximum $3,000 per animal or full depopulation with state indemnity which could net a maximum $1,500 per animal. Seale said she secured the federal USDA indemnity funding in February though she “had to use the connections I knew in Washington, D.C. to get that funding otherwise they were going to wait until April to even decide when the funding was going to come. But as it turned out it didn’t matter anyway because the money was there and they waited until the end of July. So that’s my other beef, if they’re going to force you to depopulate, it has to be in a timely manner and one year is not timely.” Of the 300 euthanized deer, 62 were fawns that Seale received nothing for. Seale did receive the $3,000 per deer for her mature bucks. She said just feeding deer costs her about $200,000 per year.

“They appraise the animals and obviously I didn’t get $3,000 per animal,” Seale said. “I did on my bucks, but my bucks were worth twice that. I’m getting 50% of what they’re worth. As an example, last year before I was a positive I had one of the bucks sold as a breeder for $15,000 and I got $3,000 for it.”

Seale said she and her legal team are fighting to gain what they believe to be “fair market value” for the property that was lost, but she isn’t banking on successfully fighting the government in court.

“With my connections and my advocacy for the industry, little Joe Blow doesn’t stand a chance,” she said. “So that’s my goal. Fix the broken process on the state and national level.”

The final battles Seale fought with state officials was how to euthanize her animals. She refused sharpshooting fearing the chaos that would’ve caused in her pens. The injection drug she and her veterinarian wanted to use was denied because it contained barbiturates, which were viewed as harmful to the environment. She paid for the drugs and veterinarian services eventually used to euthanize the animals.

“Nobody can even imagine,” Seale said. “I tell people if my animals were truly sick, I could’ve understood being depopulated. But they weren’t and that was the hardest part seeing those animals just get thrown on a trailer and loaded out.”

As she looked over her empty pens on Aug. 1, Seale said her future is unknown. She feels God has a plan and will guide her toward her next path. She believes a huge rainbow that spread across her farm after a brief rain shower the Sunday night before depopulation began was a sign from above comforting her and telling her things at some point will be OK.

Seale doubts CWD exists in Taylor County’s wild herd, but believes there hasn’t been enough deer sampled to be definitive. She’ll never know for certain how it hit her farm. She scoffed at criticisms that the deer farming industry has taken for the spread of CWD because, as she can attest, no deer farm wants this disease. Every deer that dies on a farm is tested for CWD. There are rectal biopsy live tests for CWD being used in some parts of the country. Accurate live tests would be a game changer for farmers. Seale said a researcher was begging her for eyeballs of positive deer in his attempt to help develop a fast test that hunters could use to quickly determine if deer they harvest are positive, but the state said no.

“It’s good that we test all of our dead ones,” Seale said. “No matter what they die of, even this doe that was my first positive, she showed no clinical signs but yet we caught the disease. It’s great because I hadn’t moved my bucks yet, because I might have moved the disease. That’s why it’s important to test every single one that dies. Our program works. It’s not fool proof. It’s not designed to be no-risk or zero risk. It’s designed to be low risk.”

As the vice president of the state’s

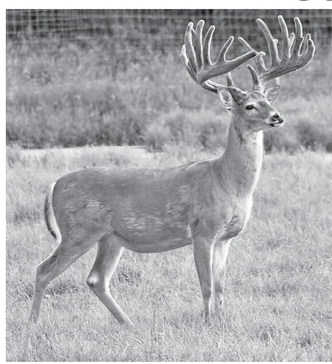

“There’s no explanation for how a farmer feels when you watch those antlers grow and you see what you’re producing from year to year.” — Laurie Seale main deer farming promotional and lobbying organization, Whitetails of Wisconsin, it’s no secret Seale is an outspoken advocate for the deer farming business. If that was a reason state officials seemingly dragged out the process, she said it’s not going to stop her from fighting for deer farmers who get hit with CWD.

“They’re telling me I can bring on other species after the clean-up is done,” Seale said. “I can’t bring in deer for five years and then even if I do there could be restrictions. But I loved my genetics. I don’t want to buy Joe Blow’s genetics and start over. I loved what I raised. I was proud of what I did. I have no desire to raise sheep, goats, cattle. Deer was my passion. There’s no explanation for how a farmer feels when you watch those antlers grow and you see what you’re producing from year to year. There’s no comparison.”

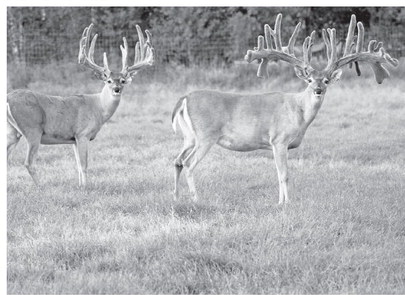

Maple Hills Farm owner Laurie Seale said 32 Stitches was one of her absolute favorite bucks. The non-typical had an incredibly rare 45-inch inside spread. He is pictured with a buck named Max Express.SUBMITTED PHOTOS