CPZ estimates impact of winter spreading ban

By Kevin O’Brien

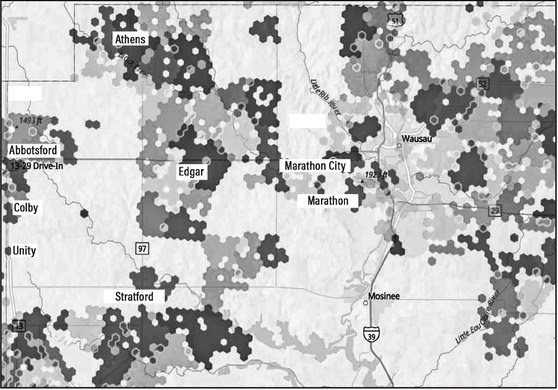

After crunching some numbers, Marathon County officials believe a proposed ban on manure spreading during the months of February and March would affect approximately 62 farmers in the county and prevent an estimated 16,000 pounds of phosphorus per year from entering local rivers and streams.

For the third time in the last four months, staff from Conservation, Planning and Zoning (CPZ) spoke to the Environmental Resources Committee on Tuesday about the possibility of curtailing the application of manure during the time of the year when the ground is frozen and fertilizers are most likely to run off into waterways.

County conservationist Kirstie Heidenreich told committee members that CPZ staff have spent the last month getting input from groups that would be affected by a winter spreading ban and diving deeper into the data about the number of farms that currently don’t have the storage capacity to make it through a 60-day ban on spreading.

See WINTER SPREADING/ page 8 Winter spreading

Continued from page 1

Conservation analyst Matt Repking said he previously told the committee that about half of the county’s dairy farmers would be significantly impacted by winter spreading restrictions, but after looking closer at the numbers, he said that percentage may be slightly lower.

Of the 348 active dairy farms in the county, he said 198 of them have some sort of manure storage and 150 don’t. For the 150 farms without manure storage, Repking said only 22 – about 15 percent – of them have nutrient management plans. By comparison, 98 percent of farms with storage facilities also have nutrient management plans, which help farmers decide when and where to apply fertilizer in a way that maximizes the impact and minimizes runoff.

Repking said he used the 22 farms as a subsample and found that they had an average of 77 milking cows (between 25 to 180), and 41 percent of those farmers indicated the use liquid manure in their management plans. Eighteen of the 22 farms reported doing winter spreading in the past two years.

“So, there is a lot of manure being applied by this group during the winter months,” he said.

Extrapolating out from those numbers, Repking estimated that 62 farms in the county would need to either rent manure storage space, build new facilities or somehow change their practices to comply with a winter spreading ban.

Out of the nearly 62,000 dairy cows in the county, he said about 20 percent are on farms that need to haul out their waste on a daily basis, and 80 percent have on-site storage.

Repking said the average 1,400-pound dairy cow produces about 32 gallons of manure per day, and using that number, the average- sized herd of 77 cows (for farms without storage) would generate 150,000 gallons of waste every day. That number increases to 340,000 gallons per day for those with 180 milking cows.

If the county’s farmers were to agree not to spread manure in February and March, Heidenreich said over 9 million gallons of manure would stay off the fields, resulting in a phosphorus reduction of 16,000 pounds over those 60 days. The cost for removing this amount of phosphorus at a municipal sewer treatment would be $3.2 million, according to CPZ’s estimates. Heidenreich said these estimates do not account for the waste from farms that have storage facilities but still spread manure during the winter for the sake of convenience.

“That number is probably far greater than 16,000 pounds of phosphorus,” she said.

The Wisconsin DNR has told CPZ staff that if the county does not reduce its phosphorus load going into the Wisconsin River Basin, it will inevitably put more pressure on municipal sewer utilities to reduce their output, resulting in more costly upgrades and higher sewer bills, she said.

A question of cost

The most pressing concern for farmers who don’t currently have enough manure storage space is the cost of building new facilities.

Based on the most recent cost estimates, Heidenreich said a new concrete vertical wall storage structure would cost between $60,000 and $80,000 for an average-sized herd of 77 cows. A much cheaper option would be an earthen lagoon, which is estimated to cost between $25,000 to $35,000 to accommodate a larger herd size of 180 cows.

Heidenreich said this is in the same price range as a new septic system for a rural residence, and if the county were to implement a winter spreading ban over three to five years, she’s confident that most farms could set aside enough money or get financial assistance.

Repking did point out that these cost estimates do not include any transfer systems, which can get pricey. CPZ’s estimates were only for structures to hold two months of manure.

An alternative to building new facilities would be to rent storage space from former farmers who are no longer using their pits. Repking said the most recent data showed a little over 100 idle manure facilities in the county, but it’s unknown how many would require upgrades to be operational again.

Heidenreich said these rental arrangements are a “win-win” for both the farmer who doesn’t need to build new facilities and for the pit owner looking for additional income.

“We would anticipate that it would play a huge part in the solution to this,” she said.

Supervisor Jacob Langenhahn, chair of the ERC, said he’s still worried about the financial impact of requiring farmers, especially with smaller operations, to either build or rent manure pits for a couple months of storage.

“I get that there a lot of manure storage systems out there, but this looks like it would put a significant burden on a lot of farmers, and I don’t think my position is changing – that I don’t want to see this ban go into effect,” he said.

Tom Mueller, a farmer from the Athens area, said he struggles to understand why some farmers are unwilling to invest in manure storage or pay for a nutrient management plan, which he has had for over 20 years.

“For us, it was a game-changer because it made us a more profitable farm,” he said. “So, I don’t understand why more people aren’t adopting them. It helped us target where our nutrients went, whether it was commercial fertilizer or manure. Every field has different levels of fertility.”

Looking ahead, CPZ plans on hosting two public input sessions this month on the proposed winter spreading ban, including one in a western township. Heidenreich said CPZ staff also plan on meeting with members of the Marathon County Farm Bureau at 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 13, at the bowling alley in Marathon City.

“I know they’re anticipating a good group in attendance, so I look forward to having really meaningful conversations with that group,” she said.

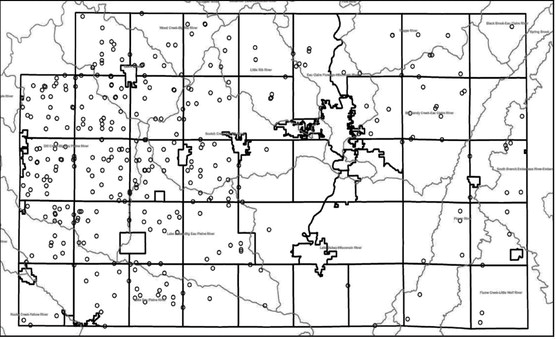

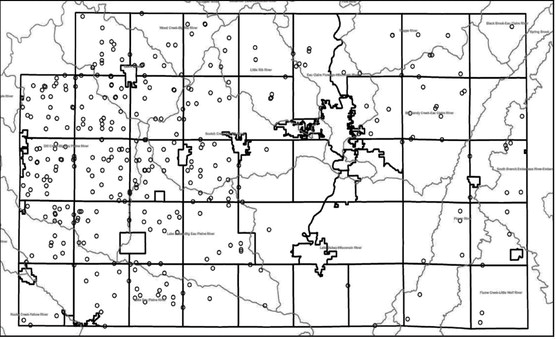

DAIRYLAND - Each dot on the map above represents one of Marathon County’s 348 active dairy farms. Conservation analyst Matt Repking said 150 of these farms (43 percent) don’t have manure storage facilities. A proposed ban on winter manure spreading has raised questions what about farmers would do if they don’t have space to store manure over the winter.