‘A little nasty’

By Kevin O’Brien

Pictures of bright-green beaches at Big Eau Pleine Park were used as a lead-in to a presentation last week from conservation officials who rolled out a set of new and old ideas for curbing toxic algae blooms by reducing manure runoff in western Marathon County.

“It’s a little nasty,” said water resources technician Jared Mader as he displayed recent pictures of thick blue-green algae carpeting beaches along the Big Eau Pleine Reservoir for members of the Environmental Resources Committee at their Sept. 3 meeting. The committee was also shown satellite images from the Environmental Protection Agency highlighting the algal blooms.

Using a DNR grant, Mader said staff at Conservation, Planning and Zoning (CPZ) have started testing water samples from Big Eau Pleine beaches for eColi and fecal coliform, but the bigger concern remains the presence of blue-green algae blooms that can cause health problems for anyone who enters the water.

“So far, our results have shown that the bacteria is very low, but due to our concerns with the algae, we’ve been leaving the advisory levels at red,” he said, referring to signs posted at the beaches to warn the public about the potential dangers of going into the water.

County conservationist Kirstie Heidenreich also shared social media posts regarding the Big Eau Pleine beaches, which contain both misinformation about the safety of the water and more accurate statements that may turn people away from the county’s biggest money-making park.

“This beautiful county park we have is unfortunately getting known for being unusable in terms of recreating in the water,” she said.

Heidenreich outlined all of the various efforts the county has undertaken to reduce the phosphorus-rich manure runoff that feeds algae blooms, such as encouraging buffer plants around waterways and advising farmers on when the best times are for spreading manure.

“We are doing everything we can but we are still seeing pictures like the ones I just showed you,” she said, noting that the images of the Big Eau Pleine look like water seen “in Third World countries.”

The Big Eau Pleine itself is not the only polluted waterway in the county, as nearly all

RUNOFF/

NO, IT’S NOT SAINT PATTY’S DAY - This recent photo of a swimming beach at Big Eau Pleine Park shows the extent to which blue-green algae blooms have taken over portions of the reservoir’s shoreline. Marathon County’s Conservation, Planning and Zoning Department is suggesting a new push to reduce the phosphorus runoff that feeds algae blooms.

SUBMITTED PHOTO Runoff

Continued from page 1

of the streams and rivers in western Marathon County that feed into reservoir are listed as “impaired” by the EPA, Heidenreich noted.

A plethora of studies and reports have made it clear what needs to be done to stem the tide of contaminated runoff into the Big Eau Pleine, she said. One of the solutions is to minimize manure spreading during the winter months when fields are frozen and covered in snow. She pointed to a study by U.S. Department of Agriculture indicating that winter manure applications increase runoff by 250 to 360 percent.

Reducing this practice is “something that can move the needle in our lifetime” when it comes to cleaning up the Big Eau Pleine watershed, she said.

Old and new ideas

Realizing that past attempts to end winter manure spreading have been unsuccessful, Heidenreich said CPZ is hoping that county supervisors and farmers will consider more incremental steps toward reaching this goal.

The first step would be to get mediumsized farms with between 500 and 999 animal units to stop winter spreading within impaired watersheds. The next step would be to lower the minimum threshold to smallersized farms with at least 300 animal units. All farms with 1,000 or more animal units, known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) are regulated by the Wisconsin DNR and are already prohibited from manure spreading during the winter.

Heidenreich said these proposals would focus solely on medium and medium-large farms that typically have the manure storage facilities needed to get through the winter without spreading.

“This would not affect small family farms,” she said. “This would not affect beef farms that have solid manure only and no liquid manure.”

Another idea is to connect farmers who do not have adequate manure storage space with landowners who have the facilities but are no longer actively farming. Heidenreich said CPZ has a database of all the manure pits in the county that could be used to facilitate rental agreements between farmers and those with unused facilities.

“That neighbor’s very happy to get a little bit of rental income from something that they aren’t even using on their farm, and that farmer’s very happy because they don’t have to spend hundreds of thousands on a new manure pit when they really don’t need one anyway,” she said. “It’s just a couple months of the year when things are really tight for them.”

Technological innovations are also available to assist farmers in keeping manure on their field, Heidenreich said. She said the county could reach out to custom manure applicators who use low-disturbance toolbars to inject manure into the soil and incentivize farmers to use them. A related idea would be to establish a competitive grant program for farmers to purchase manure flow meters for dragline injectors so they know how many gallons per acre they are applying.

Using the Fenwood Creek pilot project as a model, Heidenreich said the county could also provide funding for small-scale experiments on both large CAFOs and smaller farms that would be willing to try cover cropping or no-till farming on 50 to 100 acres of land.

The key to implementing any of these ideas is to first get buy-in from farmers and other landowners in the county, Heidenreich said, so she suggested having a public hearing to hash out these proposals.

Committee reaction

Members of the ERC seemed generally supportive of CPZ’s proposals, though they had some questions on how the county would implement them.

Vice-chair Mike Ritter said he grew up in the Fox Valley, so he’s familiar with the impacts of phosphorus contamination. He said Marathon County can’t wait for state or federal agencies to act.

“I know full well what Lake Winnebago looks like in the summertime. It’s not nice,” he said. “To see the Big Eau Pleine is worse, that’s horrifying. We really need to step up.”

Supervisor John Kroll said he likes the idea of initially targeting farms with 300 to 999 animal units when it comes to winter spreading.

“That seems like a plausible starting point,” he said. “It encompasses a lot more farms than just the big ones.”

Tom Mueller, a non-voting representative of the farming community on the committee, said he believes many farmer simply do not have enough manure storage space to make it through the winters.

“They’re adding cows, but their storage isn’t there,” he said, suggesting that every farm should have enough storage capacity for 12 months – not nine as currently recommended.

Heidenreich noted that all of the ideas presented at last week’s meeting were put in writing years ago as part of a 2011 strategic plan following a major fish kill on the reservoir.

“We know how to fix it,” she said. “The plan has been laid out for us already. We just have to be willing to take the next step together.”

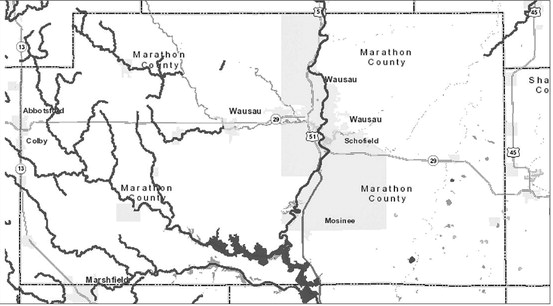

IMPAIRED WATERS - This map of Marathon County shows all of the waterways that are considered “impaired” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which means they do not meet water quality standards due to chronic contamination. All of the rivers and streams in the western part of the county drain into the Big Eau Pleine Reservoir, which is shown in the bottom center of the map. County officials have been trying for years to reduce runoff within the watershed.

SUBMITTED GRAPHIC