FAMILY E

NTERTAINMENT

Dorchester-based Skerbeck clan started with a circus in 1884

In 1901, under a canvas tent in northern Minnesota, 23-year-old circus clown Anton Skerbeck leaned forward to bow to the audience — and fell to the ground.

He had just finished a “knock-about” routine with his siblings, so the crowd understandably thought it was a pratfall, a slapstick gag meant to elicit one last laugh.

“At first it was thought that he fell for fun and one of his younger brothers, Frank, who also acted the part of a clown, ran up to Anton and gave him a slight kick,” the Dorchester Clarion reported. “As Anton did not move, Joe, the oldest son, went to him, raised him up and carried him to the dressing tent. About 400 people witnessed his sudden death.”

The untimely death, later attributed to a heart attack, was never announced to the crowd, and the rest of the Skerbeck family kept the show going, according to the troupe’s hometown newspaper back in Wisconsin. Anton was later buried in Dorchester Memorial Cemetery, under a tombstone reading “Here Lies a Prince.”

While tragic, the story is also a testament to the Skerbeck family’s unwavering determination to provide entertainment to the masses, something which they’ve been doing for over 160 years.

It’s an epic story that goes all the way back to 1857, in what was then called Bohemia (now Czechoslovakia), when Frank Skerbeck Sr. traded in his linen factory for a circus tent. His initial foray into traveling performances ended when the show went broke, but it left an impression on his son, Frank Jr., who brought the show business bug with him when he moved his family to America in 1882.

Frank Jr. and his wife Maria, along with the five kids they had at the time, settled in the still-developing Dorchester area. Their first plan was to farm the land they bought, but they soon abandoned that idea and began preparing for a life on the road as traveling performers.

Within two years of their arrival, they had built a home and a barn known as the “Old Blue Farm,” which served as a practice facility for their various acts, which included everything from acrobats and contortionists to trapeze acts and sword-swallowing (Frank Jr’s speciality). Over the next several decades, the Skerbecks performed with various other outfits and under several of their own names, including Skerbeck’s Great One-Ring Railroad Show from 1901 to 1904, Skerbeck’s Wild West & Hippodrome in 1907 and Prairie Joe’s Wild West Hippodrome & Circus from 1910 to 1911.

Eventually, the ever-expanding family transitioned from a circus show into the carnival business — something the Skerbecks continue to do to this day.

For most of their first 100 years in the United States, the Skerbecks called Dorchester home, the place they always came back to after all of their time traveling across the country.

In the Oct. 24, 1924, edition of the Dorchester Clarion, the local paper lamented the fact that the family was planning to stay in Missouri for a full year.

“We will surely miss them in Dorchester during the winter for we’re always looking forward to their return from their summer’s work, but we wish them the best of luck as we do all the Skerbecks wherever they may be for they are old residents of Dorchester country and naturally we are proud of them.”

The newspapermen understood that the Skerbecks’ chosen vocation demanded a semi-nomadic existence: “Their work is to help folks enjoy themselves and forget their worries and troubles for a little while at least, and it is surely well worth the while.”

A LONG STREAK BROKEN

2020 has marked an unfortunate “first” for the Skerbeck family. For the first time since 1884, they have not been able to hit the road — due, of course, to COVID-19.

Joe Skerbeck — the great-great-grandson of Frank Sr. — said even the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918 wasn’t enough to keep his grandfather (also named Joe) from sacrificing a season’s worth of income on a razor-thin budget.

“They wouldn’t have been able to survive a year off,” he said. “There weren’t any government programs to help anybody then, not even Social Security.”

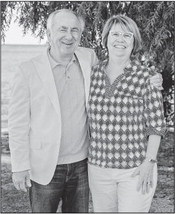

Though Joe has technically been retired from the carnival business since 2015, he and his wife Debbie are still very much involved in the family business, now known as Skerbeck Entertainment Group and based in Michigan.

Joe and Deb’s son, Jamie, and their two daughters, Tori and Niki, represent the sixth generation of Skerbecks to be involved in the entertainment business. Among their nine grandchildren, the oldest of which just started college, is the seventh generation in the making.

For 40 years, Joe and his brother, Bill, were partners in the carnival business, but that arrangement has changed.

“I retired in 2015, and he wasn’t ready to retire, so we split up the assets in an agreeable fashion, and my children bought my assets from me and took over the assets I would have had,” Joe said.

Bill and his wife CJ now own a separate carnival company, but with the surname attached, the Skerbeck Family Circus, which is also based in Michigan.

Joe was a 22-year-old college student attending Wisconsin State University in Stevens Point when his father, Eugene, passed away in 1969 at the age of 50. He and his sister, Cindy, both left college and took over the family business — something he had always planned to do.

“It’s just a great way of life,” he said. “Your family’s always there all summer long. We park our trailers next to each other so we see each other every day.”

Joe started selling balloons at the carnival when he was just six years old, and continued to work summers there throughout his childhood. After graduating from Dor-Abby High School in 1965, he got his own game concession and started adding on to that. He was planning to partner with his dad on a couple of rides when he passed away, and so instead, he partnered with his mother, Arlene.

Growing up in a family of carnival owners is a bit like being raised on a farm, Joe said, as every kid is expected to pitch in and learn every aspect of how the operation works.

“I’ve done most of the chores, except maybe the mechanized stuff,” he said. “We learned all there was, or we thought we knew all there was until we got a little more experience and learned how stupid we were.”

The on-the-road season was much shorter when he was growing up, starting in mid-May and going through Labor Day, so he’d normally only miss a couple weeks of school in the spring. Nowadays, he said the season starts in early April and goes all the way to October.

Joe said the life of a carnival worker appeals to “rebels at heart” who don’t fit into a normal 9-to-5 job “It’s a tough life. They don’t get to go home for six months in a row. Basically, they’re on call 24/7. Although we don’t work them anywhere near that, they’re always around the show.”

This routine is still much safer and more secure than the hardscrabble existence the Skerbecks entered into when they first took their show on the road in the late 1800s.

A family history compiled by Jim Jantsch at the Dorchester Historical Museum chronicles the Skerbecks’ many setbacks and successes over the years. The saga is replete with tales of accidents, injuries, tent blow-downs and other mishaps.

During an 1894 stop in Galveston, Texas, for example, the family had to rescue one of its larger animal acts from drowning in the Gulf of Mexico. They decided to take an elephant with them for a swim, but the big beast wandered out so far “only the tip of her truck was visible.” Fortunately, their animal trailer rescued the pachyderm before it went under.

“Never again did we take an elephant swimming,” Grandpa Joe was quoted as saying.

The family story also includes bittersweet moments like the death of Frank Jr., who passed away on his 74th birthday in 1921. He happened to be riding his beloved merry-go-round on the day of his granddaughter Tillie Sebold’s wedding.

“During the ride he quietly slipped away into the land where trouble never follows,” said his obituary in the Dorchester Clarion.

“He went out like a showman,” Joe said of his great-grandfather, noting that it was “the last ride of the night.”

Joe said he was fortunate to grow up in Dorchester just across the alley from his grandmother, Ida Skerbeck, and next door to his aunt, Violet Greaser, who would share stories from the family history with him. Two of his great-aunts‚ Mandy Kaarup and Pearl Weydt — who started their own carnivals with their respective husbands — both lived until 1967, so he heard their stories as well.

Oftentimes, he would assume his relatives were embellishing their stories for dramatic effect, but after doing his own research, he found out that many of them happened just as he had been told.

The Skerbecks tried out just about every form of entertainment to bring in crowds, from burlesque shows and “moving picture” projectors to Wild West acts and sideshows featuring “freaks.”

“Tastes have changed,” Joe said. “It’s kind of politically incorrect now to go see the guy with three legs or the conjoined twins.”

In the last 20 or so years, Joe said the popularity of rides over shows and games has really skyrocketed, and so has the cost of the rides themselves.

“A million-dollar ride isn’t that big of a deal anymore,” he said.

With his kids and grandkids poised to take the family business further into the 21st century, Joe said he knows they will have to continue to adapt in order to survive — just as their ancestors did. However, he’s confident in the timeless nature of their chosen profession.

“As long as people want to go out and have a good time, it’s great entertainment,” he said. “It’s affordable. There’s always great rides.”

After Joe’s mother remarried in 1972, the family started to slowly move away from Dorchester over the next 20 years, but Frank Jr., his wife Maria and several of their children remain in the Dorchester Memorial Cemetery.

Joe still fondly remembers the village as his childhood home, a place with a strong sense of community where young kids could wander around without worry and everyone took time to greet their neighbors.

“In some ways, it’s kind of like a big carnival because everybody knew everybody and you kind of watched out for each other’s kids,” he said. “You felt safe.”

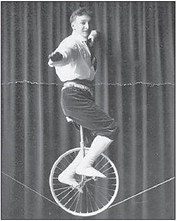

A CLOWN TILL THE END -Anton Skerbeck, pictured here in 1890, tragically passed away in 1901, at the age of 23, during a performance in northern Minnesota.

STILL IN BUSINESS -Joe Skerbeck and his wife Debbie (maiden name Vieth), left, have retired from the carnival business but are still involved in running Skerbeck Entertainment Group with their three adult children. Joe’s brother Bill and his wife C.J., right, continue to run Skerbeck Family Circus.

MAKING HIS DAD PROUD -Frank Skerbeck III performs a high-wire act on a unicycle in 1910.