Communication key to safe online experience

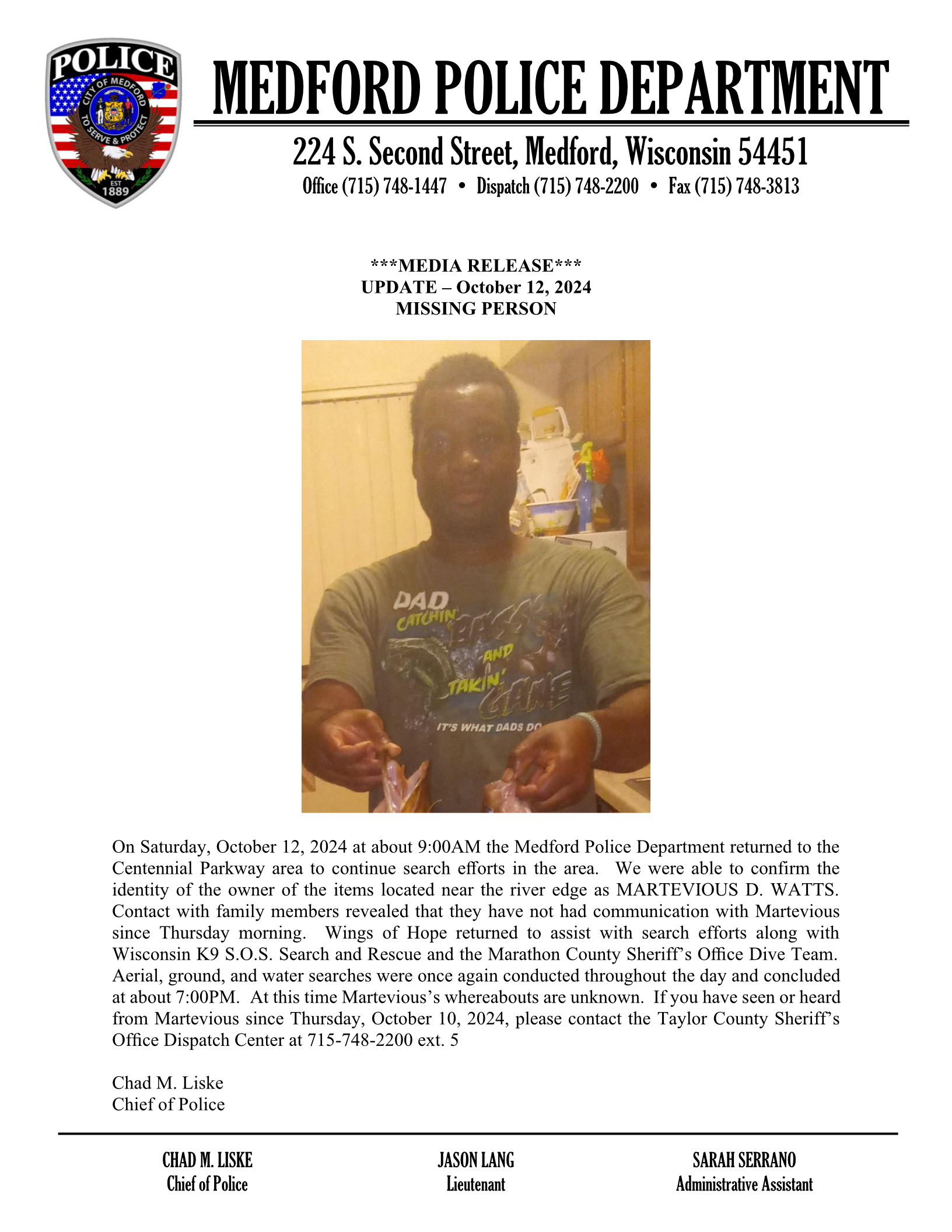

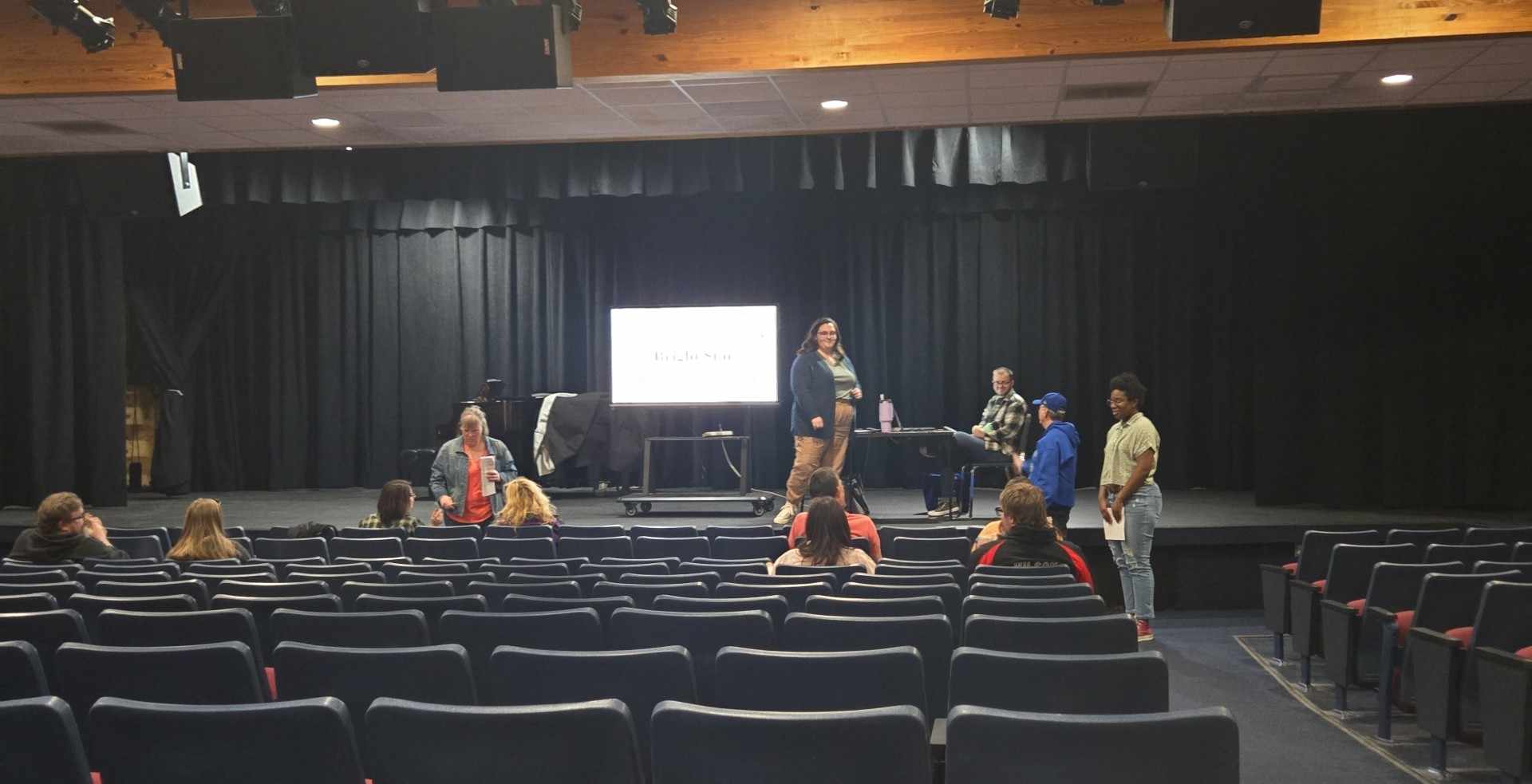

Technology can open the world to people, but also comes with its own hassles and dangers. Justin Patchin, co-founder of the Cyberbullying Research Center and UW-Eau Claire professor of criminal justice, stopped at the Cadott High School to talk about teens’ use, and misuse, of technology, with area parents and guardians, Feb. 10.

Patchin gave those in attendance the chance to ask questions about screen time limits, cyberbullying, sexting, and other topics related to youth and technology.

Patchin’s interest in youth began his junior year of college, when he began working in residential treatment with juvenile delinquents. After two years of working with the program, Patchin moved on to graduate school.

His first day of graduate school, he met Sameer Hinduja and they began to talk about their own interests, which overlapped in the interests of kids using technology and problems that came out of that combination.

“As budding academics, we looked to see if anyone was doing research on cyberbullying and of course, in 2001, nobody was,” said Patchin.

The two started their own research into the issue and began by asking kids about their experience with cyberbullying, through an informal online survey.

“We got thousands of kids that responded,” said Patchin.

He said their eyes were really opened to the problem of cyberbullying, when the youths’ responses were longer than the survey would allow.

“These kids who responded were giving us pages,” said Patchin.

Patchin says that is when he and Hinduja realized there was a story that needed to be told. They have held about 15 formal surveys in the years since, and the Cyberbullying Research Center was born. They also expanded their study to include questions about offline bullying and other adolescent behaviors online, such as social networking, sexting, sextortion and digital self harm. Their goal is to provide re-

See ONLINE/ Page 3

Justin Patchin, co-founder of the Cyberbullying Research Center, answered questions area parents and guardians had about teens’ use of technology, and any issues associated with the use. During the presentation at the Cadott High School Feb. 10, Patchin discussed research on cyberbullying, sexting and screen time limits. search, data and evidence for problems kids are encountering online.

A theory Patchin has formed over the years, is that much of youth behavior online is related to their familiar relationships.

“My idea of virtual supervision, is if you have a strong bond with your parent, when you are out with your friends, you’re going to act as if your parent is there, even when they’re not,” said Patchin.

Patchin said the idea could also work with a favorite teacher, coach, mentor or anyone else the child would not want to disappoint.

“The idea is, to try to get children to think a little bit about their behavior, even when the adults aren’t necessarily right in the room,” said Patchin.

Patchin says cyberbullying often comes in the form of messages and peaks during the middle school years, before dipping down through high school and college.

“That’s pretty similar with what we see with regular school bullying,” said Patchin.

Despite the easy access to technology, Patchin says bullying is still more common in school, than online. Patchin also noted most kids, 85-90 percent, who are cyberbullied, are also bullied at school.

Patchin says he hasn’t seen evidence that cyberbullying is more prevalent in large schools, than small schools.

“It happens in schools of all different sizes,” said Patching.

He did give anecdotal evidence that cyberbullying may not be more prominent in smaller schools, but it “blows up” more in a smaller school, because everyone knows each other, and there is less flexibility to switch classes or friend groups.

Patchin says technology can be demonized, but there is nothing inherently bad about it. Social media is just where kids are hanging out, so that’s where you see problems. In some cases, Patchin says youth may not even realize what they are saying is hurtful, and they may try to be funny or show off to a friend.

“They don’t see the response, so they don’t know how that’s affecting you,” said Patchin.

Patchin also says there is overlap between victimization and offending, where children who are bullied may retaliate or bully someone else in response.

Despite the rash of apps that promise users an anonymous experience, Patchin reminded those in attendance that nothing online is ever really anonymous.

Through research, the center also tries to counter the fear- based messaging parents often encounter. Patchin used the issue of sexting as an example. He says their research shows sexting does happen, but not as frequently as it is made out to happen, with only 25 percent of youth reporting they partook in the behavior.

“It’s not as bad as you see in the media and most kids are doing the right thing,” said Patchin.

He says the fear-based headlines can normalize the behavior in teens and make it seem like they should do it, because they’re told everyone else is.

Patchin says conversations between parents and youth are important, but the conversations also should not be based on fear and threats. In a paper he and Hinduja recently published, titled It’s Time to Teach Safe Sexting, they argued only talking about consequences associated with sexting, like getting labeled as a sex offender or the image shared everywhere, can also cause harm.

“If we push that narrative too much, then it opens our kids up to exploitation,” said Patchin, adding it is important to give children an out, so they are not pressured into more acts, in fear of repercussions. “Whatever threats you make or whatever consequences you talk with them about, you also need to preface that by saying, ‘If anything happens, talk to me and we’ll work through it.’” Patchin says their paper comes at the issue from a harmreduction model, to minimize risk of prosecution and distribution of the image.

Patchin says they tell youth not to show their face or other identifying characteristics, such as tattoos or birthmarks, so if the image is distributed, people will not be able to tell who is in the photo. He also said suggestive, instead of explicit, images are the safer option.

Patchin also talked about screen time limits and age-appropriate technology. “Every kid is different,” said Patchin.

His advice to parents is to get their child a phone when the child is a little bit younger than the parent thinks they should be. Patchin says giving kids the device when they are still bonded with the parents, as opposed to their friends, makes the phone seems like a privilege, and monitoring usage becomes common and accepted.

“You want to instill good practices,” said Patchin, adding easing youth into the power technology holds is a good idea.

As for screen time, Patchin says he is more interested in the nature of the screen time, than the raw number of hours.

“Sitting and playing a first-person shooter game for 10 hours is a lot different than doing a learning app, or interacting or creating,” said Patchin.

Even activities like watching videos is OK, if it is not interrupting other activities.

“My ultimate message is making sure to keep that line of communication open between kids and adults, so they (kids) don’t feel trapped in a negative situation,” said Patchin.

Anyone who wants more information, can visit cyberbullying. org or justinpatchin.com, to see additional research, fact sheets, blogs about upcoming research and resources.