Deep dive on drug court data reveals mostly positive results

By Kevin O ’Brien

Members of Marathon County’s Public Safety Committee plunged into a “deep dive” of data related to the county’s drug treatment courts at its latest meeting on Oct. 8, taking a closer look at how many participants successfully complete the program and go on to better themselves without committing new criminal offenses.

The presentation by the county’s data officer, Michal Schultz, was a follow-up to the committee’s Sept. 10 meeting, when county officials presented a more cursory review of drug court data that left committee members and district attorney Theresa Wetzsteon wanting more comprehensive information in order to evaluate the program, which allows those facing lower-level drug charges to avoid prosecution if they comply with treatment requirements.

Schultz went over data she received from the Department of Justice’s Comprehensive Outcome Research and Evaluation (CORE), a password-protected database with information on the state’s treatment courts and diversion programs.

“This is by far the best data source we’ve had,” she said.

According to the most recent CORE data, a total 412 defendants were referred to the county’s drug treatment court, and of those, 95 were deemed eligible for participation and agreed to enroll. Of those 95 participants, 44 graduated and 30 were terminated after violating the conditions of the program.

Seventeen remain active in the program, three are inactive and one was administratively discharged.

Among the 262 defendants who were deemed ineligible, a majority of those were kept out of the program because they had current or prior weapons violations, violent offenses or felony drug dealing charges.

Laura Yarie, the comity’s justice services coordinator, said the program is limited to

See DRUG COURT/ page 3 Drug court

Continued from page 1

those who have been a Marathon County resident for at least six months and have agreed to plead guilty, among other criteria.

Yarie said the drug court team tries to assess whether the defendant has a substance use disorder or if their criminal behavior goes beyond drug-seeking behavior. For instance, if the person has previously been charged with selling drugs, the team tries to determine if that person is doing so for the money or just “supporting their habit.” If someone is caught possessing 15 times the normal dose of a drug, or if they have been involved with a fatal overdose, they are automatically disqualified.

Ultimately, a small group of law enforcement representatives, and those from social services, probation and the public defenders office must reach a consensus on whether a person is admitted or not.

Outcomes

In trying to answer the question of whether Marathon County’s drug courts are successful, committee members started by looking at the county’s graduation rates versus statewide numbers from the Treatment Alternative and Diversion (TAD) program, which provides grant money for drug courts.

Marathon County’s current graduation rate of 59 percent is a few points higher than those measured at the the state level from 2019 to 2023.

The committee also considered if graduates are better off after participating in drug court, reviewing before-and-after data about living situations, employment status and child support compliance (employment and stable housing are requirements for graduation).

■ Of the 44 recent graduates, 27 are living independently as renters and 12 are living with friends or family. Prior to entering the program, 12 were in jail, 11 were in transitional living, 10 were living with friends or family and nine were renting or living in their own home.

■ Of the 44 graduates, 39 are working full-time, two are working part-time and three are unemployed due to disability or retirement. Before entering the program, 33 were unemployed (including 10 not seeking a job), six were employed full-time and three were working part-time.

■ Of those who had child support obligations, the rate of compliance greatly increased, from 7 to 92 percent, according to case managers.

Judge Suzanne O’Neill noted that many of the graduates who are now living with family or friends are doing so because they have been welcomed back by their loved ones.

“I think it’s clear that they’re better off,” she said. “They’re now employed, they’re now living independently or at least in a stable residence.”

One important measure of the drug court’s success, from a public safety perspective, is the rate at which participants commit new crimes. Schultz said this data is a “can of worms” because of how recidivism is defined and whether it includes new arrests, new charges, new convictions or new jail sentences.

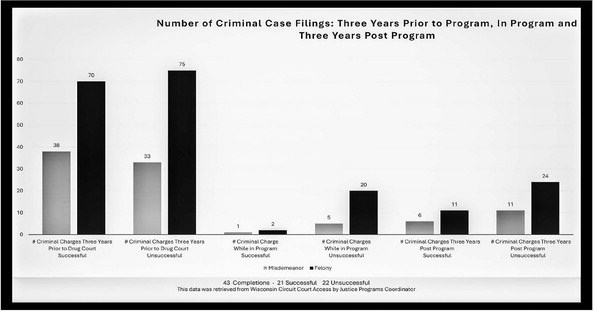

Among the latest graduates of the drug court, seven of them had “recividist events” while participating in the program, and three current participants reoffended. However, longterm data looking at the number of criminal case filings before and after drug court participation shows a marked drop in criminal activity in the three years after a person has completed the program.

In her experience, Judge O’Neill said drug court participants are most likely to violate the conditions of the program early on, simply because they are not used to following requirements such as showing up for daily drug testing or doing 20 hours of community service per week.

“Sometimes they stumble and sometimes people might think we’re too patient with them,” she said.

Still, even for those who are kicked out of the program, O’Neill said she sees some improvements in their behavior over time.

“There is some benefit even for those who don’t succeed in the program,” she said. For those who do succeed, she said it’s “pretty clear” they’re engaging in less criminal activity afterwards.

DA Wetzsteon, who has repeatedly raised concerns about both the drug court and the OWI court for repeat drunk drivers, said one of her worries is that violent offenders could be allowed into the program if restrictions connected to TAD grants are lifted. As an example, she cited a debate about whether someone could be charged with firearms possession if they have guns at their residence but are arrested somewhere else.

“Our office has certainly expressed concerns about that,” she said.

Judge O’Neill said she agrees that violent offenders should not be allowed in drug court, noting that the county has been approved for two more years of TAD funding, so it will have to abide by the grant restrictions for the foreseeable future.

Suzanne O’Neill

Theresa Wetzsteon

SIGNS OF IMPROVEMENT - The graph above shows the level of criminal activity among participants in Marathon County’s drug diversion court, comparing the number of criminal case filings three years before they entered the program, while they were enrolled and three years after.

GRAPHIC BY MICHAL SCHULTZ/MARATHON COUNTY