OWI court faces uncertain future

By Kevin O’Brien

A Marathon County diversion program that offers drunk drivers a treatment alternative to jail time is at risk of being eliminated after a state law change reduced the number of offenders who are eligible to participate.

At an Oct. 10 meeting of the Public Safety Committee, Judge Suzanne O’Neill gave supervisors an update on the county’s criminal diversion programs, including an OWI (operating while intoxicated) court for repeat drunk drivers who agree to enroll in a substance abuse treatment program to avoid a jail sentence.

Started in 2011, the OWI court has an 87 percent success rate, with 92 individuals who have successfully completed a dependency treatment program after being convicted of a felony-level offense, O’Neill said. Among those who have graduated, the recidivism rate is 18.5 percent, significantly lower than the state average of 37.4 percent, she noted.

However, after state lawmakers approved mandatory jail sentences for those with five or more OWI offenses, O’Neill said the number of participants has dropped from its maximum of 25 down to three. The program was traditionally only available to those facing their fourth, fifth or sixth conviction.

O’Neill said the court has tried shifting its focus to a different “target population,” including those who commit other crimes under the influence of alcohol or due to addiction.

“Whether or not that’s going to work, honestly I don’t think any of us know right now, but we do know that alcohol oftentimes is a factor in people’s conduct, with treatment and their addiction under control, they can be law-abiding, successful members of our community,” she said.

County administrator Lance Leonhard said he plans on doing a full report on the OWI court halfway through next year, just so board members can decide if they want to keep the program going.

“We’re down to three,” he said. “That’s not a great value for what the investment is.”

The county allocates $80,000 per year to administer the OWI court, but with the drop in participants, the staff time has been cut from one full-time person down to halftime.

According to the county’s Justice Alternatives webpage, the OWI court provides “intensive counseling, community supervision and support from a team of professionals in the criminal justice system.” Offenders participate in the program as part of their probation, and it takes an average of 18 months to complete.

Committee chairman Matt Bootz asked what would happen to the three current participants if the OWI court was discontinued. The county also operates a similar diversion program for drug-related offenses, but O’Neill said “the evidence suggests that it would be more harmful than beneficial” to transfer OWI offenders into that program.

“I really don’t know how we would service them,” she said. “The bottom line is we could not absorb them into the drug recovery court.”

District attorney Theresa Wetzsteon, however, told committee members that repeat OWI offenders are still put on probation, with an agent assigned to work with them on issues like substance abuse counseling and employment.

“If those individuals did not have OWI court, they would have the Department of Corrections still supervising them and providing access to alcohol and other drug treatment,” she said.

The drug and alcohol diversion programs do provide more intensive support than probation does, but those offenders would otherwise be in jail or prison, Wetzsteon said.

O’Neill concurred that the recovery diversion programs are for people “headed to prison” with a long history of addiction and involvement in the criminal justice system. However, she also said it can be “jaw-dropping” to see how much people can improve themselves after going through a diversion program.

“It takes a long time, but it’s just amazing how people can change and hopefully be productive members of our society afterwards,” she said.

Bootz recalled when five successful participants told their stories to the committee a few years ago when the diversion programs were under review.

“It’s sad, but the truth is, it took somebody saying ‘You’re going to prison now unless you do this program,’” he said. “That was their rock bottom.”

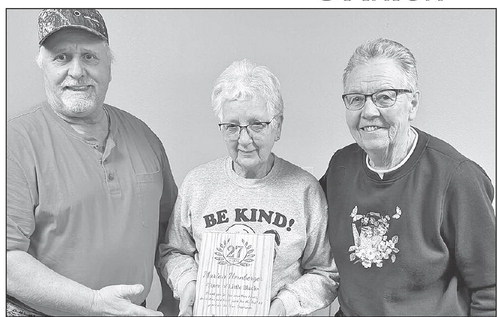

Theresa Wetzsteon