Who responds when there’s no one left to call?

By Ginna Young

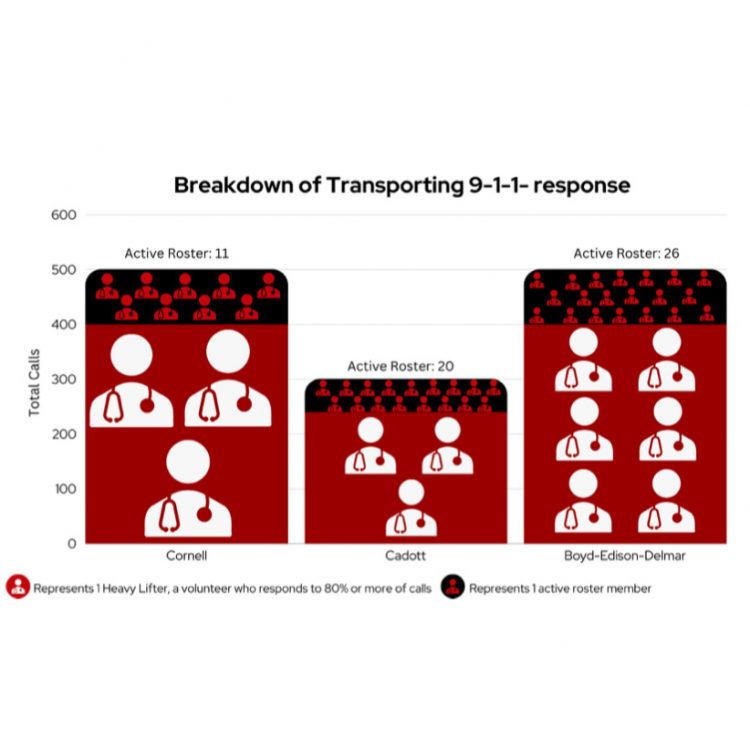

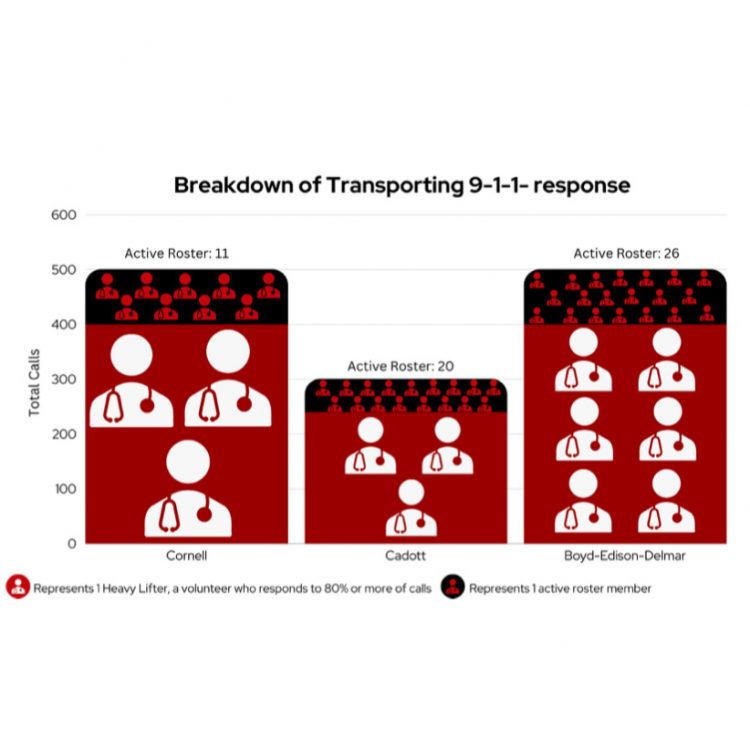

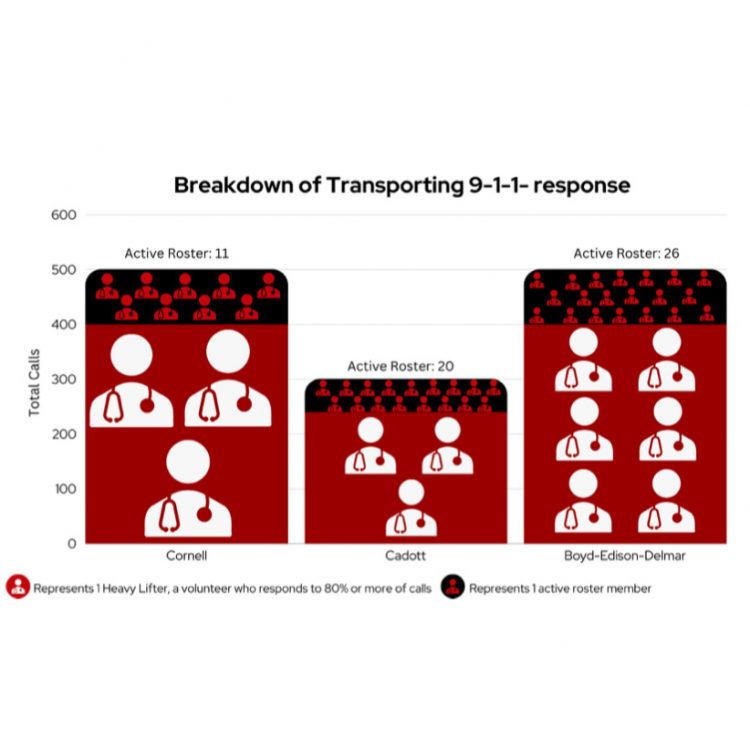

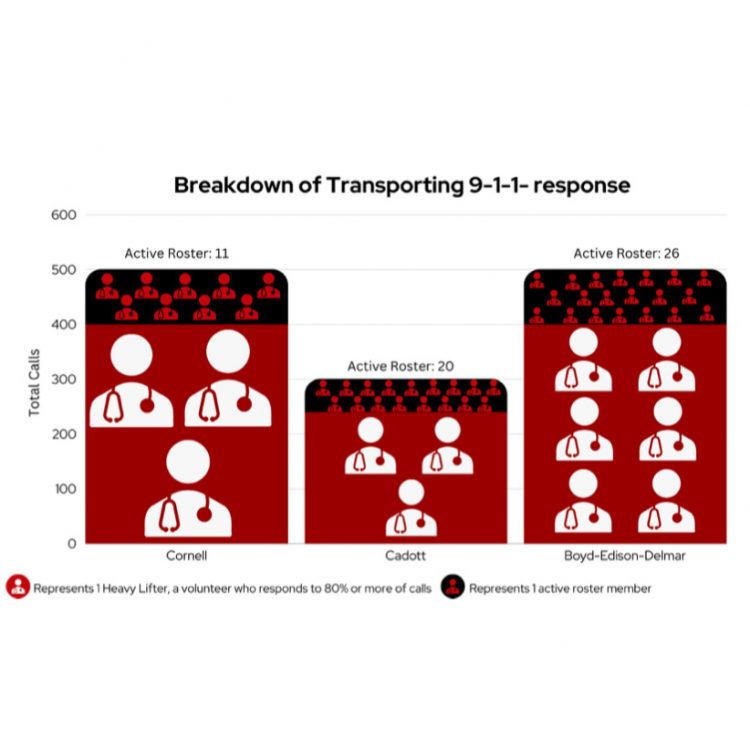

When someone is ill or injured, who do you call? No, not Ghostbusters! You call 911 and a tone goes out to your nearest ambulance service, wh...

By Ginna Young

When someone is ill or injured, who do you call? No, not Ghostbusters! You call 911 and a tone goes out to your nearest ambulance service, wh...