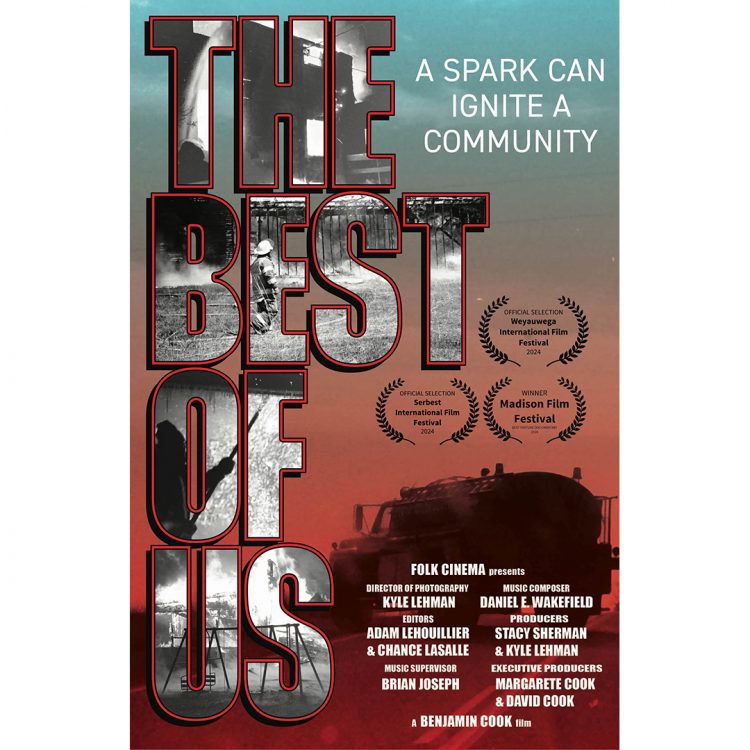

The Best of Us is igniting a spark that can’t be contained

By Ginna Young

How do you explain what a firefighter goes through in the line of duty, what it means to them, the impact it has on them and the community they serve? It’s almost impossible, unless you’ve lived that life yourself, but for Cornell native Ben Cook, he knew he had to try.

As a documentary film maker with Folk Cinema, Cook came back to his hometown of Cornell, to begin a grueling two and a half weeks of filming. Beginning in May of 2021, and ending in October of this year, the project – including a year of editing – took three years to complete.

“Several editors stepped in to help,” said Cook. The reason Cook originally had the idea to return home to film, was that he saw through social media how one of the volunteer firefighters in Cornell, Justin Fredrickson, had been shot when a handgun got overheated during a blaze and discharged, randomly striking Fredrickson.

Once Cook knew this was a project he wanted to undertake, he contacted the Cornell Area Fire Department (CAFD) and was given the go ahead to begin filming, conduct interviews and research the history of the department. In order to prepare, Cook and his team, which included a crew from Eau Claire, read as much statistical information as they could before the interviews.

The focus was at first on Fredrickson, about how he recovered, why he returned to his firefighting ways and how the community rallied around the department. But, as they started interviewing, the crew realized it could turn into something a little bigger.

Cook discovered that then fire chief Denny Klass planned to retire in the near future, and that assistant chief Matt Boulding would step in to take his place, prompting the intriguing notion of generations passing the torch.

“As we kept filming, more and more themes became present,” said Cook. “As we were filming, I was taking mental notes about what material might go where.”

After that, Cook sorted the interviews into topics and scenes, and began an arc for each of the subjects.

‘The first assembly edit was three hours long,” he said. “We discussed everything from the history of the city, to the history of firefighting, but ultimately, found that the emotional core of the film was most important.”

Finally, by recutting and reordering the film, a 71-minute version was settled upon. All that was left, was to release it to the public.

“The theatrical experience is unparalleled,” said Cook. “To sit in a dark room with family/friends/strangers and emotionally go through something, was always the way we wanted this film to be experienced.”

Once they started playing film festivals, Micon Cinema, a local theatre, was contacted about a screening for the firefighters and it only expanded from there, especially after the trailer was released. Multiple screenings were ordered and are receiving encore performances, in theatres throughout the Chippewa Valley.

“We made this film for the firefighters and their families, and I hope they like it,” said Cook. “Someone messaged me that they were going to see it a second time and that really moved me.”

For the multiple award-winning film, The Best of Us – A Spark Can Ignite a Community, the story begins in Cornell, in the early 1990s, where Cook grew up listening to fire calls on the scanner. In a small town, everybody knows everybody and on the CAFD, there’s a lot of trust and camaraderie between the firefighters.

“It’s always been that way and I’m very proud of that,” said Klass.

Times have changed since Cook was growing up, when the fire whistle blew to call the firefighters. For example, not everyone could hear the siren when it sounded, so the department upgraded to radios. Over the years, many pieces of equipment have been purchased, as well as new trucks.

A whole new building was also constructed, because the newer and bigger trucks no longer fit in the old building. All this is needed to help the 30 plus volunteers respond to emergencies, in the 246 square miles the department covers.

Unlike fire departments in large cities, small towns rely on volunteer firefighters, who do not man the station, but respond from wherever they are at the time. That could be from their place of work, their home, Christmas dinner, a party at the lake, their kid’s ballgame or birthday celebration.

That can make for some friction with spouses and family members, but for the volunteers, it’s an obligation to help out their neighbors to respond when the call goes out.

“That’s someone’s worst day and they’re asking for help,” said firefighter Tyler Burdick.

Since the 1980s, 100,000 less volunteers have joined rural departments, while 4,000 departments have closed. If that happened to Cornell, the nearest fire station is more than 20 miles away for response.

“From the time a page came in, to their response and arrival…chance of rescuing would be slim to none,” said Boulding.

Not everyone is available at one time, so mutual aid is a huge part of rural departments. Maybe this department can send a tanker, maybe that one can send three or four firefighters. No matter what, they have each other’s backs to keep everyone safe, whether it be for a house fire, an accident that requires extraction or even a lift assist for someone with mobility issues.

The good thing about rural life, is you know everyone, but it can also be bad, especially as an emergency responder. Such was the case in winter of 1996, when, be-cause of icy roads, a car went into the river along State Hwy. 178 and most of the passengers drowned, with only one person surviving.

For Klass, that was especially emotional, as one of the youth who lost his life, got his hair cut in Klass’ barbershop on Main Street.

“It was six months before I drove along that stretch of road on 178,” said Klass. “It’s something you don’t forget.”

“It is actually quite a bit easier, if you don’t know the person,” said firefighter Al Swanson.

Then, there are the times that the CAFD responds to an emergency and once the ambulance whisks the patients away, the firefighters might have to just wonder as to the outcome, unless they see the person later on. “Sometimes, you never find out,” said Klass.

Times have changed for sure, as more hours and training is needed, with students able to join the department while in high school. Having younger bodies is a plus, to keep the department viable for years to come, with several father/child duos on the CAFD. There are also women on there now, who Boulding says do the job just as well, sometimes better, and children respond to them, if needed.

“Having female firefighters is always a plus,” said Boulding.

Being a firefighter is not easy, but the rewards of helping people make it all worthwhile and the bonds of brotherhood never die. Even after the fight he had for his life, Fredrickson was ready and willing to jump back into firefighting, and venture back into burning buildings.

“There’s not a single moment I ever thought about giving it up,” he said. “It’s just who I am.”

And that is why Cook made The Best of Us, to show that determination, small town spirit and willingness to help others.

“I know I came out of this a changed person,” said Cook. “Sometimes, it takes a community to figure out who you are. I love Cornell, and I’m so very proud to be a part of it.”

In addition to the screenings locally, near Cornell, The Best of Us will also be shown in Minnesota, New York, Tennessee, Texas and New Jersey, so far, and Cook has more in the works for his home town, as he delves into the disappearance of Shannah Boiteau, in an upcoming feature documentary.

“The support has been incredible,” said Cook. “When you make something, especially when you spend years making it, you have no idea if it’s going to connect on any level. So, it’s all based on hope. For just one person to say that, was enough, to feel like that hope was justified.”